Wherein loose lips end up sailing ships, that is, a venerable fishing schooner.

Issue 140: Sept/Oct 2021

Decades into my successful marriage, I know that compromise is requisite to happiness. Which explains why, that summer, my beloved Grampian 30, Affinity, sat quietly alone at her mooring for two solid weeks while Jacqueline and I vacationed in Newfoundland, the rock on Canada’s eastern extremity she had her heart set on visiting.

After arriving in St. John’s, I quickly came to appreciate the easy informality of everything and every place we went. If I wanted fries instead of mashed, that was no problem. If I’d lost my ticket to the museum, that was OK—it was enough to explain that’d I’d paid and lost my ticket. If I didn’t make it in time for the scheduled whale watching trip, then I could take the next one. There seemed to be a cultural divide between this province and the rest of Canada; Newfoundland seemed free of silly rules and constraints. People were friendly and simply glad we’d come “from away” to visit.

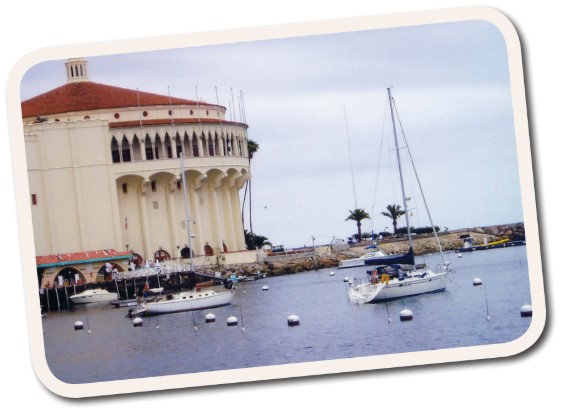

After lunch one day, Jacqueline said she had a coupon to take a trip on the schooner Scademia (Jacqueline is a planner and had coupons for nearly every activity on this trip). I was eager to see the harbor and the schooner, but when we arrived, I couldn’t hide my disappointment. Scademia was about 100 feet long and perhaps 18 feet abeam with two tall masts. She sat tethered to the dock between two much larger vessels. A man was working on the foredeck of Scademia, within earshot of where we stood.

After lunch one day, Jacqueline said she had a coupon to take a trip on the schooner Scademia (Jacqueline is a planner and had coupons for nearly every activity on this trip). I was eager to see the harbor and the schooner, but when we arrived, I couldn’t hide my disappointment. Scademia was about 100 feet long and perhaps 18 feet abeam with two tall masts. She sat tethered to the dock between two much larger vessels. A man was working on the foredeck of Scademia, within earshot of where we stood.

“I think I’ll pass on the schooner trip,” I said.

“Why? I have a coupon.”

“It’s not really a schooner anymore, it’s just a tourist barge. The aft boom has been removed to create a tent to keep the tourists out of the rain. They built a cabin around the forward mast for a gift shop or something. There are benches for people to sit on. There’s an observation deck on top of the gift shop. The sails look like they haven’t been raised in years.” My eyes traveled up to the crow’s nest. “Certainly the royals, top gallants, and yankee haven’t felt any wind in a long time. None of this would be on a fishing schooner. This is a tour boat. I imagine all they do is motor around the harbor or something.”

I suggested a place on George Street for lunch and we left, noting the sign that said the next sailing was at 2:00 p.m.

At lunch, Jacqueline reminded me that she had a coupon for the schooner and that she’d like to use it. I repeated my objection but conceded that I didn’t have a better plan for our afternoon, except for the brewery tour. We agreed to return to the dock, see what was happening, and then decide on either the schooner or the brewery.

Back at the dock, I was surprised to see a crowd waiting to ascend the gangplank. I was working on my best pitch for sampling a beverage at the brewery when I noticed the man who’d been working on the schooner’s deck earlier striding along the dock. He doffed his hat and smiled as he passed the tour¬ists, then dropped the smile and replaced it with a scowl; he was making a beeline for us. I nodded as he approached, and he took me firmly by the shoulder and led me away from the crowd.

“Earlier, you were making noises like you know something about sailing a vessel.”

“I have a sailboat on Lake Ontario,” I offered in my defense.

“You know your red greens and fore from aft?”

“Yes.”

The man leaned in closer and spoke in a whisper. “Then I’d be needing a favor to ask. There’s a music festival up north and all my crew is gone to it, except for Peter there on deck. I make a piddlin’ on ticket sales, especially with people like you keeping coupons. It’s the bar and souvenirs that keeps me afloat…so I’ll be asking this favor.”

“I don’t understand,” I stammered.

The man’s voice went even lower, “Would you be takin’ the helm for the cruise? I’ll clear her away from the dock and then turn her over to you while I go below and set out the bar and give the dialogue on the loudspeaker.”

It took me a moment to take this in. “I don’t…I’ve never sailed a ship this size.”

“You was talking pretty big to that lovely young lady with you afore the lunch.”

I glanced back at Jacqueline and straightened my posture. “I suppose a ship’s a ship…but I’ve no interest in motoring about. Once we clear the harbor, I’d want some sails up.”

The captain paused. “I’ll talk to Peter, the young lad. He can put up the lowers, but that’s all. There’s a brisk breeze out there today and I don’t want a load of tourists too sick for drink and souvenirs.”

We stared at each other before I finally said, “If it’ll help you out, I’ll do it; but keep an eye out. If I get in trouble, you’ll have to take over.”

“There’s a lad. It’ll be a great day.”

With that he put a big smile on his face and strode over to the gangplank to welcome his guests on board. I returned to Jacqueline.

“What was that all about?” she asked.

“Nothing really,” and I took her hand to join the embarking throng.

When we were all aboard, I heard the twin diesels fire up. Peter scurried around the deck making preparations to cast off. A few people from the small ticket office down the dock came out and lifted the heavy lines off massive iron mooring cleats embedded in cement, and Peter coiled them aboard. The captain put her in gear and expertly nudged her back and forth between the two huge vessels lurking fore and aft until Scademia was clear. He motioned for me to come take the wooden wheel. Jacqueline looked puzzled and somewhat apprehensive.

“The harbor gap is only 60 feet wide, so take her up the middle if there’s no other traffic,” said the captain. “Follow the red greens and you’ll be fine. Here’s your throttle. If it’s not too breezy out there and Peter hoists sails, just draw the levers back here to an idle, but leave her in gear. Off your starboard side you’ll see Cape Spear. Point your bow for the tip of the point.”

With that, he took his captain’s hat from his head, placed it on mine, then disappeared down a companionway. Suddenly I was at the helm of a fishing schooner in the middle of St. John’s Harbor. I was both thrilled and terrified.

I pushed the twin levers forward and the ship lurched. I corrected and she responded obligingly. Heading for the gap, I saw the first green marker and steered to leave it to starboard. People milled all over the decks before me, some pointing up to Signal Hill and some looking out through the gap to the Atlantic beyond the lighthouse and the surging white caps that awaited. Huge hills and cliffs soared hundreds of feet in the air all around, shielding us from wind and wave. Moving slowly through the calm waters, one couldn’t help but think that if man had set out to build a perfect harbor, he couldn’t have done better than nature did with this one.

The speakers on deck exploded: “Welcome aboard the schooner Scademia and enjoy your trip back to the time when fishermen took vessels such as this out to the Grand Banks summer and winter through all weather to fill the holds with cod for a hungry nation. As we motor toward the harbor mouth and the great Atlantic Ocean, look up the steep cliff on your left side and you’ll see Signal Hill, the site where the first wireless message was received from Europe…”

I heard the words, but I couldn’t pay attention; I was too focused on praying that there would be no vessels coming into the harbor through the narrow gap we were quickly approaching. To my great relief, it happened that only myself, Scademia, and a few hundred tourists slipped through and out into the Atlantic that day.

Out of protected waters, I felt a southwest wind tug at my clothes and try to lift my hat from my head. The seas before us started to build to 2-foot waves. As I helmed with one hand on the huge wooden spoke and secured my captain’s hat with the other, I noticed several people in the crowd looking toward me. I offered a broad smile in reply, which they seemed to take as reassurance.

I pushed the throttles forward and Scademia responded, holding a steady course out into open water. To my right I could clearly see Cape Spear in a hanging gray mist. Several people came from below with cups in their hands and Schooner Scademia T-shirts on their backs. The ship was handling well. I was gaining confidence. It was time to kick it up a notch. I spotted Peter in the crowd and beckoned him over.

“I’ll swing her around to the wind. Can you put some canvas up?”

“Looks like a great day for it! I’ll raise the two lowers.” I was surprised and encouraged by his enthusiasm, and also confused.

“How can you raise the stern lower without a boom?”

“I’ll secure a block to the stern rail and run a sheet. Give me a nod when you want them up and hold her steady to the wind.”

With that he was off and soon appeared at the mast with a few of the sturdier-looking passengers who all held fast to a halyard. I brought her head to wind and nodded. The huge rings around the mast flew skyward taking the canvas with them. The sail flapped about in the wind and I gave the throttles a nudge forward to hold her to course. With the sail up and the thick halyard cleated, Peter and his hearty crew moved to the forward mast and quickly hoisted that canvas. Once secure, Peter nodded, and I eased her to port and in just a few seconds the canvas snapped, the sails filled, the deck heeled, and we were off romping close-hauled through the waves heading straight for the point of Cape Spear.

In one sense, there really was no difference between Scademia and my 30-foot Grampian. Under sail, once I got her in her groove, I could feel her doing her happy dance. When she drifted to windward, just a slight nudge of the wheel brought her back. The tourists milled about the heeled deck and leaned on the rails, the sails were taut as Peter eased the sheets, the waves swooshed beneath the lee rail, and I stood feet astride. I caught Jacqueline’s eye in the crowd, smiling the broadest smile and looking like a television fashion model with the wind whipping her long, black hair. I felt a tug at my sleeve and looked down to see a young lad. His mother smiled.

“He wanted to come up and meet the captain,” she yelled into the wind.

“Welcome aboard, son. Are you enjoying the sail?”

“Yes sir…she’s really moving fast, isn’t she?”

“She’ll do,” I replied. “Would you like to take the helm for a short spell?”

“Could I?”

I moved to the side but kept one hand firmly on the wooden spoke. “Just step in here and take her with both hands.”

I held on tight to keep the boat on course while the young fellow moved in beside me, grasping the wheel and smiling into his mother’s camera. And with a click, I was immortalized as an ocean-going captain, not of a tourist barge, but of a true fishing schooner, Scademia.

We galloped along toward Cape Spear…more cups in hands, more T-shirts…a happy ship she was, and then Peter approached.

“Would you like the staysail up? It’ll help balance her. She’s going good.”

“Sure,” I said. “Do you need me to bring her head to wind?”

“No, just ease her up a bit to take the power out. I’ve got some hearty crew who’ll have it up in no time.”

With the staysail up she did smooth out and weather helm eased. Now she was skimming along more on a beam reach rather than close-hauled, and Peter had adjusted the sheets with the skill of an experienced sail trimmer. Throughout, the loudspeakers barked sporadically about the wooden ships and iron men of the Atlantic provinces, about John Cabot first discovering St. John’s Harbor in 1497, about sailors finding the Grand Banks and the cod so thick you could jump overboard and walk across them without sinking. Then I heard, “And to your right is Cape Spear, the most eastern point of land in Canada…and now we’ll be coming about and heading back to St. John’s Harbor.”

Coming about? “Peter!”

Peter emerged out of the mass of bodies. I didn’t need to ask—he could see the question in my eyes and laughed.

“The staysail is self-tacking and I’ve good men on sheets for the other sails and they know what to do. Hold her steady for another five minutes while I get everything ready, then yell, ‘Helm’s alee’ and swing her around. It’ll be fine.”

A few moments later, the speakers boomed again. “Ladies and gentlemen, we’ll be coming about in just a minute, so find something to hold on to and secure your drinks. Ready when you are, Captain.”

I took a deep breath, felt the eyes of the crowd upon me, looked up to the sky, and savored the wind in my face and the firmness of the wheel in my hands. “Helm’s alee!”

With that I spun the wheel, spoke after spoke slapping my hand. Scademia lurched and for the briefest moment, with my heart in my throat, she paused with the waves splitting to either side of her hull, then slowly eased through irons onto the port tack. The headsail slid across over everyone’s head, the big boom came across the deck with the sails flapping only momentarily. Peter scurried to move the block and sheet on the stern rail over to the starboard side before the wind filled the sail.

I looked to the bow, and I’d gone too far around. With the wind now astern and the open sails, we were bobbing out into the Atlantic and perhaps Europe. But just a gentle pull on the wheel and she righted herself again. Peter moved from one line to another and sheeted the sails in until I had her dancing along again, steering a bit high of the harbor mouth off in the distance. The sails were filled with powerful gusts, the sun shone, and we were on our way. I was captain of all I surveyed.

Approaching the gap, I turned to windward, and Peter dropped and secured the sails. I motored half-throttle into the gap. Alcohol and the near certainty of surviving the voyage infused the crowd, and their singing was more boisterous than it had been heading out. Even so, my mind was on one singular thought; “Red, right, returning. Red, right, returning.”

Once inside the harbor, I swung south and motored past Scademia’s mooring spot. I couldn’t believe how small the space was, those huge tankers towering over on either end. I swung the bow around and headed back. There was no one at the dock to catch the bow line that Peter was preparing to toss. I motored just past the empty space and slipped the levers into neutral. All I could do is try to parallel park like a car on a busy street. My hand went to the levers ready to pull back into reverse when I felt a hand on my shoulder and the captain’s hat lifted from my head.

“I’ll take her now, Skipper,” came the captain’s voice, and I breathed a heavy sigh.

“All yours,” I said as I left the wheel and walked into the singing mass of humanity to find Jacqueline.

Within minutes Scademia was nestled into her mooring spot. People had appeared from nowhere to catch and secure lines, the gangplank was dropped, and the chattering mob wobbled off the boat to steady themselves on dry land once again. Jacqueline slipped her arm through mine saying, “Hey sailor…that was fun, wasn’t it?”

I looked around and couldn’t see Peter or the captain, and so Jacqueline and I walked down the gangplank together and stood for a moment looking back at Scademia. Peter appeared on deck. I waved him ashore and he came to greet us.

I shook his hand and said, “Is the captain available? I’d like to buy you both a beer.”

Peter looked back to the boat. “Would love to, but we’ve got to clean up for the dinner cruise. Apparently, it rained at the music festival and everyone is on their way back, so we’ll have a full crew tonight.”

“I understand,” I said. “Tell the captain she’s a fine ship and it was a pleasure to be aboard. I appreciate the opportunity.”

Jacqueline took my arm and we started away down the dock. “Well, Skipper, you’ve had a rough voyage. I think you’ll need a beer at the brewery tour and then a short nap before supper.”

I looked down into those beautiful, deep brown eyes, that smiling face, and thought to myself, Davies, sometimes…in spite of yourself…you do make the right decision.

D.B. Davies is a sailor, writer, and frequent contributor to Good Old Boat. He sails Affinity, his 1974 Grampian 30, around Lake Ontario. After extensively researching the men and sailing schooners of Canada’s Maritime provinces, he wrote a dramatic screenplay about the famous Bluenose and her skipper, Angus Walters. You can find out more at thebluenosemovie.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com