James Baldwin needs no introduction to most sailors. He’s the guy who went twice around in a modified Pearson Triton and now makes wonderful modifications to other people’s boats from a home base in Brunswick, Georgia. When we’re lucky, he writes about those refits for the readers of Good Old Boat.

James Baldwin needs no introduction to most sailors. He’s the guy who went twice around in a modified Pearson Triton and now makes wonderful modifications to other people’s boats from a home base in Brunswick, Georgia. When we’re lucky, he writes about those refits for the readers of Good Old Boat.

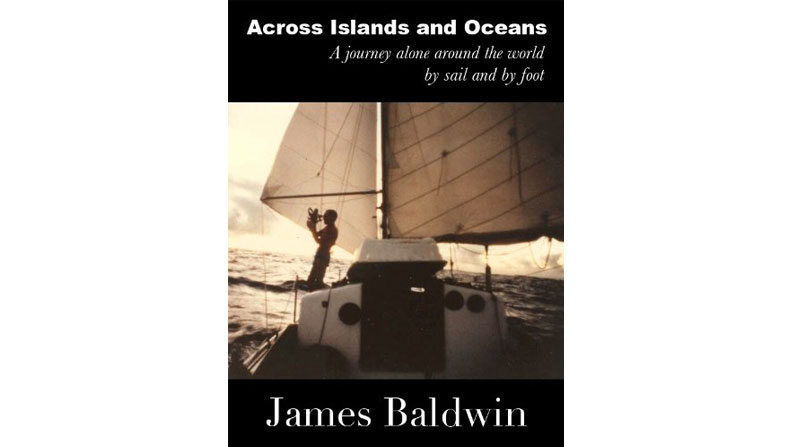

How did a 20-something with a mechanical aptitude and very limited funds decide to go off on a major voyage on a Triton? In Across Islands and Oceans, his new book written 25 years after the fact, James reflects on his early upbringing and the steps that led to the adventure of a lifetime, one that was soon followed by a second circumnavigation that may very well be the subject of a second book.

In looking back at his logs and photos, James brings the wisdom of maturity and the knowledge of how it all turned out in the end to the telling of a tale about the robust energy and spontaneity of his youth. It’s a very useful perspective and gives the book a special kind of depth. Every so often he drops in a pithy philosophical nugget, one of those quotable quotes that will endure. For example: “Looking back now I see that, in time, we become more learned and less wise.” Or: “You can talk about doing a thing until everyone finally talks you out of it or you can actually do the thing” (in this case, going off on a great grand adventure in a 28-foot Triton).

James was no ordinary young guy. (Are those who venture forth ever ordinary? Or is it their adventure itself that raises them from the ordinary?) Now, in retrospect, he ponders briefy about what motivated him and concludes that the sailor with the greatest influence might have been Jean Gau and his book To Challenge a Distant Sea. Certainly, James named his Triton Atom, just like Gau’s 29-foot Tahiti Ketch.

From that entry point, however, James’ voyage diverged from that of Jean Gau. As he went along, James discovered a side of himself he had not yet known. He realized early that he should try to meet the people who inhabited the islands he visited, rather than socializing exclusively with fellow cruisers. That led him to walking around an island and meeting many local people along the way. Soon he began climbing each island’s highest mountain and really getting to know members of inland tribes and isolated communities. He occasionally was invited to stay with local families, often ate with them, and sometimes they cured him of illnesses beyond his own abilities to mend.

His first circumnavigation took only two years, primarily because James realized that, for a sailor with no money, life on land was too expensive in customs duties, occasional marina bills, and shopping sprees. So he crossed the Pacific, Indian Ocean, and Atlantic in great long leaps, which unfortunately left much out.

It can be said that, due to financial constraints, James did not take time to smell the roses on this voyage. However, it can also be argued that each time he did make a stop, he explored the area more extensively and met more local people than most cruisers do.

His tales of the hikes and the people are as fascinating as the stories of his voyages and times at sea. This book is a wonderful addition to anyone’s cruising bookshelf and likely to become a classic someday. We liked it so much that it’s on our list to be produced as an audiobook. So if you’re not a reader, there’s hope. We’ll soon read it to you!

I hope James will have enough success with this first book to decide to write the next . . . his book about the second circumnavigation aboard Atom that soon followed.

Across Islands and Oceans: A Journey Alone Around the World by Sail and by Foot by James Baldwin, 2012 AtomVoyages.com ; 370 pages)