Wherein a foolhardy notion and a puff of wind nearly end in disaster.

Get a bunch of sailors gathered around a table at the club and they’ll tell stories. Sometimes the stories are yarns in which 6-foot swells become 10-foot waves, and 20-knot winds become a 30-knot gale, and most sailors understand that and enjoy the tale for what it is. If the story involves calamity and distress—and they often do—the nature of the crisis usually centers around equipment breakdowns or rigging failures, and always at the worst possible times. Seldom do you hear an account that hinges on the complete and absolute stupidity on the part of the storyteller.

Well, dear reader, you’re about to.

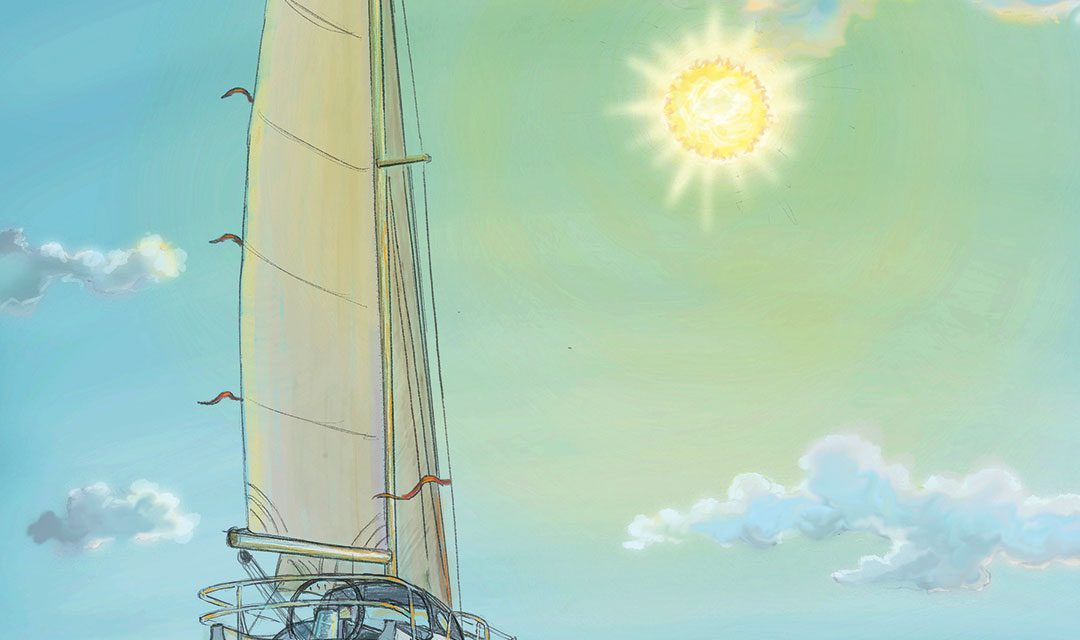

It happened on Lake Huron, on a hot, windless August day. We were two experienced sailors aboard a 31-foot Contest named Centaur, taking about two weeks to sail up into Georgian Bay and then over to Manitoulin Island and into the North Channel, time permitting. But this day, our first having left Sarnia early that morning, was proving that while we might have plans, Mother Nature sometimes had other ideas.

After sailing 10 miles out under a gentle breeze, the entire lake now spread endlessly before us, flat as pudding on a plate. There was not a breath of wind. Sails hung lifeless from the top mast like heavy boudoir drapes. It had been that way for over an hour and we’d hardly moved a few yards. After the first half-hour, we contemplated turning on the Volvo diesel and motoring to Kincardine, our first planned stop. It would take several stinky hours at 5 stinky knots under power. We opted to leave all the sails up and the autohelm on and just relax. Our plan B was Bayfield, a port much nearer that had a good selection of pubs and a nice marina. We were in no hurry, we had two weeks.

I had my computer with me and went to the bow to write. My sailing partner, Bill, sat reading in the cockpit. We were, to use an expression I’ve come to loathe, “dead in the water.” If this kept up, we’d have to turn on the engine just to get to Bayfield. The hours passed, there were no other boats within sight, and we bobbed like the proverbial cork. The sun beat down like a pile driver.

The glare from the placid water bounced up and stung the eyes. The sweat poured off me, and after about 45 minutes I’d had enough. I shut down the computer and walked aft. Bill was sprawled across the cockpit, trashy novel still in hand. He was beginning to look like a lobster. I reached over the stern rail and lowered the swim ladder.

“I’ve had enough,” I said, taking off my shirt, shorts, and shoes. “I’m going in to cool off.” With that I climbed over the lifelines and dove head first into the water.

I thought I would die.

Plunging down, I felt every inch of my being numbed to immobility by the teeth-chattering cold. I quickly turned upward and reached desperately for the surface. Once my lungs filled with air again, I wanted to scream from the shock. My goose bumps had goose bumps, yet with an ache in my groin from my testicles turning to ice cubes, I suppressed all displays of discomfort. I even turned the twisted look of agony on my face into a broad, forced smile.

“Oh man…that…is…incredible. I feel alive again. This is like a warm bath.”

Bill peeked his head over the railing, putting his book down. He looked at me questioningly. I could barely move my tingling arms to tread water. My fingers were icicles.

“This is fantastic. Can’t believe it,” I crooned.

Bill shrugged, then stood up, climbed across the lifeline, and jumped in feet first. He stayed under a long time and I got worried, and then his head exploded above the water. He was shouting epithets even before he emerged from the depths, none of which can be repeated here, or probably anywhere in polite company, ever. By now, I had little feeling anywhere in my lower extremities, but I did manage to laugh at his glaring eyes and screaming mouth.

Then we felt it…across our shoulders and head. We saw tiny ripples fluttering what had been a polished piece of blue marble. Both of us turned as a puff of wind hit the sails and the boat skittered away, about 50 feet. We turned to look at each other, and I’ll never forget the look of resignation on Bill’s face. His eyes said it all: “We’re screwed.”

I’m no great swimmer, but it was obvious that Bill wasn’t going to do anything. I felt another puff of wind and the boat slid further away. I started swimming as fast as I could toward it, head down in the water, arms flailing, and feet kicking in a frenzy. I kept my face in the water, focused, pushing myself as hard as I could until I ran out of air. I looked up gasping and was no closer to the boat. Around me, the ripples had grown and multiplied on the water’s surface.

I took another breath and plunged forward swimming once more, as fast as I could. When I lifted my head again, I was gaining, but I was also swimming off course, veering to one side and quickly running out of energy. Keeping my head above the water, I swam using just my hands, aiming for the swim ladder.

The ripples flattened, the surface turned smooth as a sheet of plastic again, and I was gaining on the boat. I found strength to keep going, but I was too slow with my head out of the water, and I knew that with one more gust of wind I’d be finished. I took a deep gulp of air and put my head down. This time, instead of frantic flailing, I pulled through each stroke, trying to keep the power in each left and right stroke even. I quickly felt I needed air but knew I couldn’t stop, that this might be my last chance at staying alive. I didn’t feel the cold anymore, just my own desperation.

And when I felt I couldn’t go another stroke, when I’d have to lift my head to breathe, my right hand hit something hard and I clutched it with all the strength I had left. I lifted my head and felt a cool breeze. I was hanging onto the swim ladder and being pulled along at about 3 knots by a now freshening wind that flapped in the sails.

Focusing on the muscles in my arms and hands to make sure that my grasp was secure, I hung on, breathing hard, until I could feel some strength returning. Slowly I pulled myself toward the now-outstretched ladder, and it seemed like the boat was trying to shake me off. I wouldn’t let it. I pulled myself forward until I could reach up with my left hand for the second rung…then my right hand for the next rung…then my left foot on the bottom rung, slowly, deliberately, knowing any mistake would be fatal, until I finally climbed over the stern railing and collapsed on the cockpit floor still gasping for breath.

I knew I couldn’t rest. If I got too far away from Bill, I’d never find him treading water in the vastness of the lake. I got up on my feet, released the jib sheet and then brought the boat about in what was becoming a steady breeze. The main filled on the opposite tack and I looked for my disappearing wake. It seemed like I’d swum a mile, but Bill was only a few hundred yards back, still treading water.

I came alongside him and swung the wheel to bring the boat head-to-wind. Slowly, Bill paddled over to the ladder and climbed aboard. We looked at each other but said nothing, not a word. I grabbed the jib sheet and cleated it down. Bill reset the autohelm. The sails filled and the boat picked up speed.

Both of us sat in the cockpit lost in our thoughts of what could have happened. What would they have thought when they found the ghost ship Centaur sailing up the lake with no one aboard? No doubt they’d come up with some bizarre theories, from pirates to the plague. Even with a deployed swim ladder as a clue, who could guess that two sailors would decide to jump into the freezing water, together, without a tether, and leave the boat with the sails up and the autohelm on?

Later that night over dinner and a bottle of very expensive wine in one of Bayfield’s most exclusive restaurants, we spoke of our next port of call and how long it would take to get there, what provisions we should buy before we left in the morning, how long it would take, and much more. But we did not talk about what happened that hot afternoon on Lake Huron. Ever.

That was many years ago. Bill has passed on now. When I think about it today, I still wonder why we never spoke about it. Perhaps it was just too scary, or maybe we were too embarrassed. Yeah, maybe that was it.

The Takeaway

We tend to think of life-threatening sailing moments in terms of a series of events that cascade together to create the danger. A slowly leaking through-hull that should have been fixed, a frayed line that should have been replaced, a weather warning that should have been heeded, charts that should have been updated, or flares that should have been replaced. The takeaway here is simple. One moment of inattention, one frivolous decision, can be just as deadly. Sail safe.