Being designated deck boy on the family sailboat was sometimes scary, always exciting.

Issue 144: May/June 2022

Dirty, difficult, dangerous. Those were the kinds of jobs assigned to me as our family’s deck boy, especially when I got old enough to go up in the boatswain’s chair to fix a loose spreader, take the helm in the rain, hank on the genny and hoist the main, or lug blocks of ice with tongs from the marina down a splintery dock in the blistering heat to the icebox.

Did I shrink from this duty? Quite the opposite. These jobs predisposed me to my later career as a commercial fisherman. I came to relish the wet, the cold, the salty, the heart-thumping as much as the calms, the skies, the beauty of the sea and the creatures that lived there (though even now I quail at the thought of going up a mast).

Did I shrink from this duty? Quite the opposite. These jobs predisposed me to my later career as a commercial fisherman. I came to relish the wet, the cold, the salty, the heart-thumping as much as the calms, the skies, the beauty of the sea and the creatures that lived there (though even now I quail at the thought of going up a mast).

One hot, sticky, summer afternoon on the Chesapeake Bay circa 1967, when I was 11, remains sharp in memory as a kind of ur-deck-boy experience.

Dad snores away below (whenever the wind quit, he liked to wait for a breeze by flaking out on a berth for a catnap). He produces great, stentorian gusts that could have propelled us had we been able to funnel them into our sails.

I stretch out sweating on the cabintop in the brothy air. Mom sits in the cockpit at the wheel. Carousel, our 35-foot yawl, slops about, sails slack, rigging slatting.

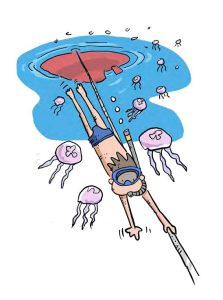

I gaze at the jellyfish (sea nettles) bobbing beside us. They crowd the water in such profusion I could use them as stepping stones to walk ashore, only a mile or so away in the haze. Even with my newly acquired lifesaving patch, which Mom has stitched onto my navyand- white striped Speedo, I wouldn’t have the grit to swim to anyone’s rescue through that mass of translucent bulbs and undulating, stinging tentacles.

Half a mile to starboard, a red-and-white lighthouse protrudes straight from the water, looking like a 19th-century planetarium marooned in the Bay. The paint is cracked and peeled, the portholes boarded up. An automatic horn mans the lighthouse solo. We sit as stationary as the lighthouse itself. But things are happening.

Half a mile to starboard, a red-and-white lighthouse protrudes straight from the water, looking like a 19th-century planetarium marooned in the Bay. The paint is cracked and peeled, the portholes boarded up. An automatic horn mans the lighthouse solo. We sit as stationary as the lighthouse itself. But things are happening.

In the sky above the western shore, spidery clouds crawl toward us and soon entrap the sun in a kind of sickly haze. Overhead, white wisps scoot eastward fast. I look back toward the twin spans of the Bay Bridge that stretch 4 miles from the western side of the Bay to the Eastern Shore. Clusters of opalescent clouds drooping like mammoth pearls sweep off to the southeast—mammatus, a portent of storms. My unease grows as fast as the sky is changing.

Mom sees that the skipper’s nap ends well shy of 40 winks.

Topside, Dad starts the engine and tells us to drop the sails. We douse the genny and main. Dad slips Carousel into gear and throttles up. Our wake ribbons over the mercury-slick water as we run for Gibson Island just a few miles distant. The lighthouse at last drops astern.

We motor into the Magothy River, a darkening sky dead ahead, and thread our way from marker to marker toward Sillery Bay.

The sky now takes on a greenish cast. The galleon- shaped uninhabited islet of Dobbins Island appears to port.

I blink, blink again, and realize that a palisade of rain is sizzling toward us through the heavy stillness. It wipes the land from view. Fat, hard drops snap on the deck, leaving splotches like bullet holes. The drops peck against my skin and scalp. Then the full force of rain descends. Dad tells us to go below. Mom bolts for shelter but I stay in the cockpit.

I blink, blink again, and realize that a palisade of rain is sizzling toward us through the heavy stillness. It wipes the land from view. Fat, hard drops snap on the deck, leaving splotches like bullet holes. The drops peck against my skin and scalp. Then the full force of rain descends. Dad tells us to go below. Mom bolts for shelter but I stay in the cockpit.

We might have sailed under a waterfall. Cables of rain fall straight down, boiling the water and sending up raindrop explosions over the deck. Dad steers by compass, somehow avoiding running aground. Rainwater streams over us. We spit seawater that splashes aboard, our hair flat as the coats of seals. Behind the sound of the deluge, thunder rumbles.

Some atmospheric switch is flipped and the rain fizzles as we close toward Dobbins Island. Can we anchor up and batten down before the storm hits?

Not so, deem the weather muses. The blackest clouds of the storm charge toward us. The light dims and the water ahead of us turns cold gray and frothy with whitecaps as the wind pummels it.

Dad tells me to get the anchor ready, and I jump below and scramble to the forepeak. I haul the anchor and line up through the forward hatch. The wind races closer. Clouds crisscross above us, running before a tremendous silver-black cloud shaped like an inverted trumpet. It scours the water below it with blasts of gusts.

I stand on the foredeck, transfixed.

The edge of the cloud sweeps over. Its opening leads upward into the tube of the cloud. The wind blares down. Carousel heels over hard, the rigging thrumming. I cling to the pulpit with one hand, clench the anchor with the other. I crane my head and stare straight up into the heights of heaven.

The edge of the cloud sweeps over. Its opening leads upward into the tube of the cloud. The wind blares down. Carousel heels over hard, the rigging thrumming. I cling to the pulpit with one hand, clench the anchor with the other. I crane my head and stare straight up into the heights of heaven.

Another blast of wind heels Carousel harder. Is she going over? My feet slide on the slick teak deck. The temperature plunges 20 degrees, stippling gooseflesh over my entire body, my Speedo no more protection than a thong. Lightning shatters the sky beyond the trailing rim of the cloud, the horizon black behind it. Rain veers down almost at the horizontal. Amid the tumult of thunder and rain and wind, I hear Dad shout for me to drop the hook.

I let it go and crawl to the forward hatch. I drop down onto a berth and slam the hatch closed, then shiver my way aft to the main cabin. Dad climbs down from the cockpit and slides the main hatch closed.

Carousel bounds on the seas that have sprung up with the wind. The portholes slosh with suds like the windows of commercial washing machines. Rain hammers on the cabin roof.

Dad inches open the hatch to check the situation. All is blue-white flashes and black sky and bombination. My anxious mind snags on a story Dad has told us before about seeing St. Elmo’s Fire dance around a sailor’s helmet once when he served as a Navy gunnery officer in the Pacific during WWII. The sailor manned an antiaircraft gun during a night attack when a storm hit. He had no idea his helmet danced with green fingers of light. But lightning hadn’t struck, that time at least, and the sailor even survived the war. Still, I dread the thought of seeing it anywhere here, now, aboard Carousel.

Dad inches open the hatch to check the situation. All is blue-white flashes and black sky and bombination. My anxious mind snags on a story Dad has told us before about seeing St. Elmo’s Fire dance around a sailor’s helmet once when he served as a Navy gunnery officer in the Pacific during WWII. The sailor manned an antiaircraft gun during a night attack when a storm hit. He had no idea his helmet danced with green fingers of light. But lightning hadn’t struck, that time at least, and the sailor even survived the war. Still, I dread the thought of seeing it anywhere here, now, aboard Carousel.

Two shotgun blasts right outside the portholes jolt me out of my St. Elmo’s reverie and send Dad topside. I pop my head out. The anchor line, acting like a scythe, has sliced down the forward stanchions of the port lifeline and piled them up by the shrouds.

But the shrouds and anchor hold, and we ride out the rest of the storm anchored from almost amidships. The squall passes and we see where we have ended up—within 50 feet of the lee shore, stumps of an old dock, sandy beach, bluff, woods— on the other side of Sillery Bay from Dobbins Island. We discover the real reason for the anchor disaster: The bow chock let go.

The anchor has dug in so deep neither the entire Carousel crew pulling on the anchor line nor Carousel under power can budge it. I find myself clinging to the swimming ladder as the designated diver. I peer at the waiting jellyfish.

The anchor has dug in so deep neither the entire Carousel crew pulling on the anchor line nor Carousel under power can budge it. I find myself clinging to the swimming ladder as the designated diver. I peer at the waiting jellyfish.

I secure my mask. I force myself into the water—even though its warmth comes as a relief after the squall’s chill— and swim quickly to the anchor line. I pivot face-first and pull myself hand-over-hand down the line into water so murky I am blind. I bump against soft masses of jellyfish every few inches but somehow escape getting stung. I grab onto the chain and reach bottom so fast my arms plunge up to the elbows in goo before I can stop.

Two dives later, I free the anchor and surface in a swarm of black, muddy bubbles, a few jellyfish lolling nearby.

In many ways I remain a deck boy aboard our own little catboat to this day—shivering in chilly Buzzards Bay waters while scrubbing off the algae and barnacles is my specialty—though I long ago gave up wearing a Speedo. I haven’t, however, given up a secret wish: that one day I will see St. Elmo’s Fire, and that when I do, I’ll be as lucky as that sailor so many years ago in the Pacific.

Craig Moodie lives with his wife, Ellen, in Massachusetts. His work includes A Sailor’s Valentine and Other Stories and, under the name John Macfarlane, the middle-grade novel Stormstruck!, a Kirkus Best Book.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com