A little nip and tuck on a used spinnaker makes for an inexpensive upgrade

Issue 150: May/June 2023

John raised the chute before cutting it to get a sense of what it might look like when he was done.

One of my most memorable sailing days was crossing the broad mouth of the Chesapeake Bay’s Potomac River in my Cape Dory 26, Skua. In a light and fickle breeze, I set a new-to-me crosscut spinnaker that someone had recut to an asymmetric. Ghosting along in 5 knots of breeze in flat water, with a soft gurgle from the bow wave and sails full and gently tugging, Skua skimmed along as the sun faded into dusk. It was a perfect finish to the day.

I have had a love affair with spinnakers ever since. I learned to fly a symmetric chute solo on my 28-foot Bristol Channel Cutter, Bucephalus, but it was a handful even with her great stability and self-steering gear. While racing on my current boat, Nurdle, a Bristol 35.5, I’ve learned a lot about spinnakers from my experienced crew. But what about singlehanding? I was certain that a symmetrical spinnaker wouldn’t be feasible on this bigger boat.

Looking for a single-handing option, I found a used, well-priced, triradial spinnaker on Craigslist that was about the right size. Its 1.5-ounce cloth seemed like an advantage for cruising, and it came with a snuffer, making it a manageable proposition.

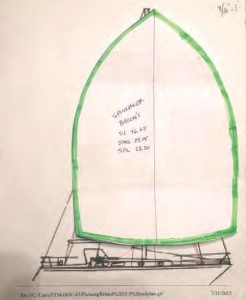

Before purchasing the sail, John made a pattern based on the dimensions of his boat to be sure it would work as intended.

But after using it a few times, I realized that it was just a little too long on the luff, which meant it would not set well except at deeper-reaching angles. Also, the heavier cloth nearly doubled the weight and bulk, making it harder to use and stow. The triradial pattern precluded shortening the luff, which wouldn’t solve the weight problem in any case.

A new sail wasn’t in the budget, but my memory of that evening on the Potomac inspired a solution: recut an old spinnaker to suit my current needs.

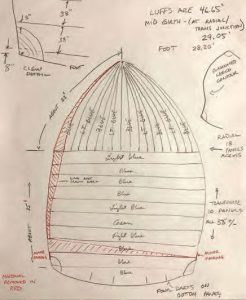

Before picking up tools to start disassembling the sail, John created a detailed diagram of it. This shows the proposed recut of the lower transverse panel and leech marked in red.

I wanted this to be a quick and easy project, which meant not building new corners. I thought I could take the excess material out of the middle, and the experts at Sailrite gave me some good advice. I wanted the luff to remain undisturbed, so correct initial luff length was important. The usual formula gives a luff length a bit over the forestay length, but I wanted it a little shorter to clear the pulpit, allow better visibility, and enable me to snug down the luff for tighter reaching.

I found a good potential candidate at Bacon Sails & Marine Supplies in Annapolis, an elderly ¾-ounce radial-head spinnaker with crosscut bottom panels for $204, including shipping. Before confirming the purchase, I cut out a scale pattern of the sail and laid it on a drawing of Nurdle’s sail plan. This was a little tricky, because unlike flat working sails, spinnakers are built with a lot of draft, and there is some guessing involved in the shape. But it seemed to fit luff length as well as clew position for sheeting.

Sail in hand, the first step was to stake it out and confirm the measurements, make a detailed diagram, and fine-tune my scale model cutout. I had considered taking the wedge out below the radial head area, but the model suggested that a lower wedge a bit above the clew would give a better shape.

Next, I took the sail down to the boat on a near-calm morning and hoisted it to check the fit. As expected, the luff length was good. I bunched up the clew to approximate the new, shorter leech dimension to confirm that the sheeting angle would work. The overall shape appeared OK, although there was excess depth in the leech, especially up high, which I thought I should trim. This would flatten the aft edge, move the draft a bit more forward, and make a slightly better reaching shape.

John used clips to hold the leech edge tape in place before putting it back on the newly sewn edge.

I then repeated my diagram and scale drawing. I planned to use existing seams as a cutting guide. I would remove one radial head panel on the leech and one half of a transverse panel above the clew reinforcement, fairing in the shortened leech between the two points. All three corners would be essentially undisturbed.

I used Sailrite’s guide to find the correct needle and thread size. Sailrite carried the required V-30 thread in a 16-ounce spool of 12,000 yards, costing $38 and enough to last several generations of amateur sailmakers. As an alternative, on the internet I found Gutermann Tera 80 thread as a high-quality, same-size equivalent, 100 percent polyester, UV-resistant, and available in a reasonable 800-yard spool for several dollars.

Once I had ordered the thread, it was time to overcome my innate reluctance to disassemble the sail. Using a seam ripper, I removed the edge tape from the entire leech. Leaving the main part of the leech for the time being, I then removed the radial head panel up to the reinforcing layers near the head. It was easiest to remove the multiple layers of head reinforcing with a hot knife, using the seam as a guide.

In the radial head area of the sail, John used a hot knife to remove multiple layers of reinforcing, with the seam acting as a guide.

I took the seam apart above the transverse panel as well. Conveniently, the sail is 343 inches wide here, and I was removing a 34-inch-wide panel. I marked the panel in 10-inch increments and placed a cutting mark 1 inch higher at each successive mark, tapering the removed sailcloth from 0 at the luff to 34 inches at the leech. For this section, I used a 60-inch drywall ruler as a guide when cutting with the hot knife.

Since I was taking out a triangle, the new hypotenuse edge was longer than the adjacent edge. Pulling both edges snug, I made marks so the fabric tension would be correct at the seam. As the leech is a complex curve rather than a straight line, I calculated the incremental change between the radial area and the transverse seam, and after marking in from the existing leech, trimmed this away with a hot knife. Some minor fairing was required at the new transverse seam to achieve a smooth curve.

Putting seamstick tape at the marks and pins in between to ensure correct fabric tension, I started reassembly by sewing the long transverse seam back together. While it seemed good when I checked at the beginning, it wasn’t until the end that I saw that my thread tension was incorrect, requiring me to resew the whole 27-foot-long seam. I then put the luff edge tape back in place, holding it temporarily with bulldog clips before sewing. The leech tape was too long, so I cut and overlapped it at the new transverse seam for strength.

The recut spinnaker now has a better shape for reaching, and is lighter and easier to handle.

I had hoped that the luff would not require any attention, but after sewing the transverse seam, the 10-to-1 taper was too much for a fair curve, so out came the seam ripper, allowing some edge tape removal for a little hot-knife fairing of the curve. After I sewed the luff edge back in place, it had a better shape. A small piece of the leftover fabric patched a small tear, and I was done sewing.

Time for the test hoist. It seemed to set well; the tack and clew were where I wanted them, the curve of the luff and leech were fair, and the overall shape and draft were what I had hoped, given the limitations of the test.

The aft-most part of the transverse seam may need some touch-up, but that can wait until after sea trials. Back in the snuffer and sailbag, the sail’s weight and bulk are greatly decreased. It’s easy to get on deck and no longer monopolizes the cockpit locker.

Overall, this was a satisfying project that wasn’t as daunting as I’d anticipated. And now, I’m ready for the next perfect sailing moment.

John Churchill grew up a boat-crazy kid in Indiana. He built a raft at age 6, sailed Snipes as a teenager, and worked his way toward salt water and bigger boats. He has sailed a Cape Dory 26 singlehanded to Bermuda and back, and a Bristol Channel Cutter transatlantic with his father. Now in Florida, John sails Nurdle, a Bristol 35.5 (and former repo) that he’s rehabbing for extended post-retirement cruising.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com