Restoring a Dyer Dink 10 for dreamy daysailing

Issue 151: July/Aug 2023

We hauled out our 1983 Sabre 30, Ora Kali, on a blustery day last November. In retrospect, we should have done it sooner. Winter comes early to the Maine coast, but I hated to see the boating season end. I had my rowboat, but oh, how I longed to be able to sail on pleasant winter mornings. I wanted a sailing dinghy.

The town we live in has lots of boaters, so my husband, Tom, and I started a search by putting a notice in the town newsletter and eyeing the racks of dinghies at the boatyard. I had my thoughts on a Dyer Midget and when a friend said there was one moldering under the deck of their house, I jumped at the offer to take it off their hands. Sadly, though it was a good little rowing dinghy and a fine replacement for the plastic rectangle WaterTender we had been using, it turned out to be an unknown model with no sailing parts and no way of finding out how to rig it.

Chi had been sitting unused for a while in a backyard in Connecticut.

Chi sits on sawhorses in the author’s yard.

Turning to the internet, Tom found a Dyer Dink for sale in Connecticut. A Dyer Dink? I had never heard of it. At 10 feet, it was larger than I had been thinking of, but the description sounded good: “A Philip Rhodes design, called a ‘real boat’ as opposed to the Dyer’s line of Dhows.”

We borrowed a friend’s truck and drove nine hours to Norwalk, Connecticut, on a monochromatic day in February. The dink sat right side up under a tarp in a tiny backyard. Joe had bought her with restoration dreams and apologized about switching to a powerboat better suited to his family, but the Dyer Dink thrilled me. I looked into her nicely painted swimming pool blue interior and ran my fingers lightly over her transom, where years of sun erosion around long-gone stencils had created ghost letters in the fiberglass that spelled out Eel Wind. We transferred her from the owner’s trailer directly into the truck bed. I was afraid Joe would realize he was giving up a good deal, and since my heart was already full of dreams of my own, we didn’t bother to even turn her over to examine her bottom before driving home with her tied in, feeling more like fishermen than sailors. It was kind of cool.

My dreams of jumping quickly onto the ocean were dashed once we transferred the dink upside down to sawhorses in our yard. That’s when we found damage to the fiberglass around her centerboard trunk. I don’t think it would have changed our minds, but there it was. Before any sea trial could commence, we had some serious work to do on our now-renamed Chi.

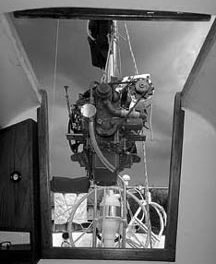

A hole was cut in the centerboard

trunk before the new plate was set in

place.

The original reinforcement in the centerboard trunk shows damage and delamination.

Chi’s very old sail has #895 on it, a number that indicates she was probably built in the late 1950s. The first Dyer Dinks from the 1930s were wood lapstrake before Dyer switched to making “Dyeresin” boats. The complete line of dinghies — from the Midget, which cruising boats sometimes carry, to the larger 9 and 12 ½ Dhows, to the Dink — is still available new from The Anchorage in Warren, Rhode Island. Even so, surprisingly little is available online about the dink. I did find a bunch of enthusiasts at the Riverside Dyer Dinghy Association in Riverside, Connecticut. This section of the Riverside Yacht Club frostbites Dyer Dinks (“easy to learn and difficult to master”), fields up to 40 boats at the start line between October and March, and holds championship regattas. I joined the RDDA forum. No, I can’t race from Maine, but I feel connected to the group.

When the weather turned toward spring, with our big boat still in the boatyard, we flipped Chi right side up and determined that delamination on the underside was caused by a wooden plate fiberglassed into the centerboard trunk to accommodate the centerboard lever (the dink has a true centerboard, not a daggerboard). At first it seemed dire; the trunk fiberglass is pretty thin: Did we need a complete rebuild? But when I suggested we cut out the old wood plate and fiberglass a new one in, Tom liked the idea. Fiberglass is nasty, prickly stuff, but it accommodates odd shapes and boat corners.

After shaping a new plate, we had to be sure before fixing it in place that the centerboard would: a) still fit in the trunk and b) turn without binding at either end. Tom drilled a hole in the plate for the bronze insert that accommodates the lever. The centerboard did fit tidily into the repaired trunk, so we jiggled the plate until the holes lined up and the centerboard could move with the lever. This took a lot of frustrating finagling, and in the end, faith that our final positioning would work with the boat upright in the water. Tom then fixed the wood in place with fiberglass fabric and resin, and primed the repair so it was ready to be painted.

The new marine plywood reinforcing panel over multiple layers of 1708 fiberglass laid up on a temporary backer. The template for locating the centerboard shaft hole is in the background.

For a 60-plus-year-old sailing dinghy, Chi is in remarkable shape, partly because she is so simple. Her fiberglass hull was built to last, and aside from the centerboard trunk, needed no repair. The gelcoat shows its age with scuffs and dings and the occasional thin patch, but after Tom buffed and waxed her, she shines. A new coat of light blue paint spruced up the interior, and we chose hard green bottom paint because she will be dry-sailed off the beach. At some point a keel guard would make sense to protect the bottom from the rocky/gravelly beach at launch and retrieval.

A bottom view of the centerboard opening, showing the extent of new fiberglass at the repair area.

All other hull features are made of teak. The two-part gunwale and rubrail are riveted through the top of the hull to each other. The wood has sustained injury over the years but survived well enough for us to add a classic canvas bumper screwed on to protect the top and edge.

The aft thwart curled badly at the forward edge where it was not screwed down. Tom removed the teak plank, wrapped it with wet cloth and covered it in plastic to let the water soak in, then clamped the wood to a pallet for a few days to dry. When the thwart had mostly flattened, he throughbolted it to flanges formed in the original fiberglass hull.

Chi has a two-part mast and a boom all made of spruce. The mast collars are in good shape, and the wedge-shaped ends fit snugly together and are sound. The mast step is good. The lower mast section had been repaired by a previous owner, and it’s unclear how sound it will be going forward, but for now, other than gluing new leather into the boom jaw, I didn’t make repairs or adjustments. She is rigged with proprietary bronze Dyer parts, and her chainplates are bronze tubes that fit through sockets braced by the forward thwart and are held in place by clevis pins and cotter rings. The arrangement provides for crude but not fine length adjustments.

Chi’s aft thwart was badly curled. After soaking in wet cloths and bags, it was clamped until it flattened out.

I bought 3/32-inch 7×19 rigging wire and tiny swages and thimbles, then borrowed a swage tool to run a new traveler as the old one had worn through. Working with the tiny rigging bits was frustrating, and I decided to put off replacing the forestay and shrouds until I had her on the water a few times and could judge whether I needed to adjust their length for stretch. I wrapped tape around a meathook in the headstay to buy time.

The sail has been patched multiple times. I like the light blue color and it’s usable for the time being, but as I intend to sail through the winter, albeit in sheltered waters, I’ll either make a new one or find a used sail. Even her running rigging is usable for now; though its stiffness makes it hard to handle, keeping it will give me a chance to see what I want to replace.

Much as I would have loved to rush Chi into the water when the basic work was done, Tom was concerned about flotation. It’s common for small boats to have positive flotation for a long time, but this isn’t always the case. And while Chi is a choice frostbiting boat because she’s dry, she can turn over or, more likely, swamp. We collected chunks of blue foam off the beach that had escaped from broken-up docks, and Tom cut a piece to fit under the aft thwart and tied a couple of boat fenders to the forward thwart. It’s enough until we decide how much of the interior volume to sacrifice to flotation.

Chi’s interior repairs have been primed prior to the finish paint job.

Chi’s rudder has been checked out and repainted.

Chi’s rudder and centerboard and the bronze hardware are in decent shape. Since the tiller looked like it was made from nice wood, Tom stripped its white paint off for an aesthetic touch.

Finally, on a sunny September day, we strapped Chi to the set of wheels we use to move dinghies and canoes, and rolled her out of the front yard. We got her across the street and down the first few yards of the steep dirt drive to the beach before she settled into a rut and the boat went one way, the wheels the other. At 135 pounds, she’s much heavier than my rowing dinghies. We were able to round up a neighbor to help lift her off the wheels and carry her to the water’s edge.

For this first test, I only had oars. She floated without any leakage around the trunk repair, and once I pushed her off the gravel and could climb in without getting too wet, she rowed very well. I was able to raise and lower the centerboard. It was a bit stiff, but that stiffness would keep it from floating up into the trunk.

Since that first sea trial, I have rigged Chi’s spar and enlisted my friend Maya to sail on the bay several times. I grew up sailing small keel boats but raced centerboard dinghies in college and owned several Dyer Midgets. I enjoy the intimacy of a small boat, being so close to the water and feeling the whole boat as an extension of my muscles and skill. A friend gave us an Opti dolly, which we hacked to make it work for the longer, heavier Dink, and I leave the mast rigged because even the two-part spar is awkward for two people to step and impossible for me alone.

Tom and neighbor Ted ready to launch Chi for the first time.

Launching with a fixed rudder from the beach in front of my house has proved difficult for Maya and me, and Tom is making a kickup rudder. Like other new boat manufacturers, Dyer has supply issues and can’t immediately provide gudgeons for the new rudder. Until they do, Maya and I are raising the sail but not stretching the foot out on the boom, rowing to water that’s deep enough to attach the rudder and crank down the centerboard before tying in the sail. One of her proprietary shroud fittings has a small crack, and this, along with other things I find as I learn more about Chi, will be addressed in another refit.

I attained the dreamed-of sailing dinghy for cold, crisp, early winter mornings. These days, people talk about “mindfulness.” It’s hard to adequately describe my feeling of complete freedom on the water. I’ve discovered that to successfully sail Chi, my body must become her extension — my hand on the tiller, my weight the animate, intelligent force that not only keeps her upright, but also helps guide her. My house faces one harbor, and with Chi I can sail through narrow channels between islands into the bigger harbor where Ora Kali’s mooring is, and tack and jibe easily through the obstacle course of winter floats.

The author, thrilled at sailing her new little boat.

Chi has also been teaching Maya the things that a small boat knows. Maya’s young. She tells me Chi is a bridge between herself and the ocean. “I can feel myself beginning to understand how the earth moves when I’m sailing.” These are Maya’s earliest words in the language of sailing, and they show a willingness to pursue fluency.

Chi also brings the two of us closer as we learn to sail her together. Maya says, “Out here on Chi we are both young children learning from our elder, the sea.” But when she’s content to sit facing forward at the middle thwart, tweaking the sail and talking about her dreams extending into the future beyond boats, leaving me to talk to Chi, it is pure fulfillment.

Ann Hoffner has been a sailor since she was 9 years old. For the last 20 years she’s written about her adventures for a variety of sailing magazines. Along with Tom Bailey, her husband and a photographer, she downsized from their offshore passagemaking P-44, Oddly Enough, to Ora Kali, a nimble, shoal-draft Sabre 30 that is teaching them the joys of Maine coastal cruising.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com