A cruise leads to a harrowing experience and an important lesson for newbie sailors.

Issue 155: March/April 2024

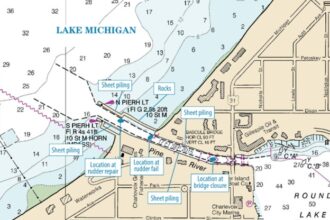

It all started when I found an available mooring just a few yards’ walk from our beach house in Little Compton, Rhode Island, on the eastern shore of the Sakonnet River. Having a nearby mooring fed our dreams of casual, easy evening sails in a little daysailer. Then came advice from everyone about needing a bit of privacy at our age, so the desire for at least a little cuddy cabin moved us to look for something a bit bigger than a 17-foot open boat.

My wife, Sue, objected to having a boat and trailer in our yard to mar the view of the water, which merged with my engineer brother Roger’s advice. He reasoned that if we’re going to be wintering in a commercial yard, why not consider the benefit of boats on which people are not the ballast?

Onward we went to search for slightly bigger keel boats and found our wonderful 1986 Catalina 25, which we named East ‘n West. We may be newcomers to the sailing world, but even with the occasional stressful conversations that all newcomers have — when raising the sails, dealing with a balky furler, or just missing the mooring buoy — our family and friends know I am only joking when I call the boat “Bob and Sue’s Folly.”

This past July, though, an encounter with the unexpected led us to put all kidding aside. After hearing our experienced sailing neighbors later say in good faith congratulations, “Great, you just survived your first catastrophe!” I fought the urge to scream, in an equally good faith reply, “Are you out of your minds?” The experience taught us to never, ever pass up a personal check of the standing rigging after a spring boat launch, and especially after mast-stepping.

Oh, the sadness of it. Our boat had been put in the water and had the mast stepped and tuned by the yard several weeks earlier, and we had already sailed it 10 miles downriver to our mooring. We had our newly minted ASA 101 certifications in hand — an earlier cert I had achieved in central Texas, of all places, had become permanently misplaced, but it always helps to go over things again anyway. After a three-week interlude, we were back in Rhode Island and ready to sail.

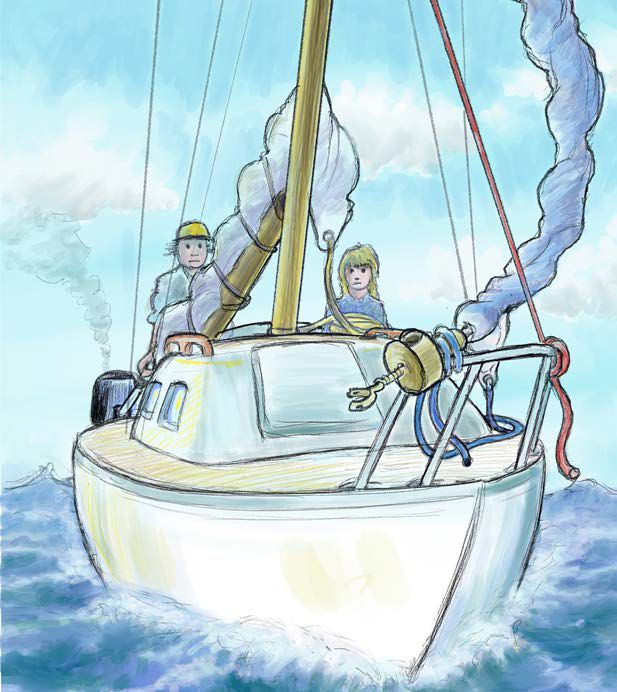

With four or five days of shakedown sails that served as short confidence-building exercises, we were finally underway with a good breeze and Sue comfortably at the tiller. Our very experienced neighbors were sailing too, coming upriver from the Sakonnet Yacht Club to meet us and hail us as hardy sailors at last. I was on the phone with them to arrange visual contact when a sickening banging and slamming sound came from the bow.

Do you know what it is like to see the furler completely free of the bow chainplate while trying to sail? Do you know how wildly it can swing and bang when you have the genoa fully filled and trimmed? Luckily, my complete inexperience kicked in, and without regard for life or limb, I went forward, laid down, and started to furl the sail by hand. Do you know how hard it is to control a boat, much less steer it into the wind, when a fully unfurled genny and the front stay are loose? Difficult is an understatement.

Sue tried as best she could, while trying to decipher my stressed comments that were flying into the wind. I’m not sure it is possible to hand-furl a fully deployed 150% genoa under normal conditions without the leverage of the furling line, but I am assuming either a divine hand or an unusual amount of adrenaline — or both — came into play, and I somehow wrestled it into a near-fully furled position.

Isn’t there a saying about there being no atheists in a foxhole? The bow and foredeck with a detached forestay swinging around your head is pretty close. Also, it didn’t help that my usual difficulty with spatial relations had me unfurling the darn thing at first. Next, in an act of inspiration, if not sheer desperation and fear, I grabbed a nearby line and somehow lashed the darn furling drum to the nearest bow pulpit stanchion (in memory, I was not calling it darn).

After calling our neighbors to let them know we were all right despite the scream they heard as I threw down the phone when the forestay separated, we gingerly tacked and ran with the wind behind us back upriver toward our mooring — until, doing the quick geometric analysis in my head, I realized we were sailing without any meaningful forestay. Another stressed comment followed and we dropped the mainsail. With the faithful Tohatsu 9.8 chugging along, we made it back without incident.

The next morning’s inspection showed that the clevis pin had fallen out of the forestay toggle, and the toggle had deformed and spread as it ripped out of the chainplate. Evidently, somewhere along the line, someone had forgotten to replace the cotter pin that held the clevis pin securing the toggle to the chainplate — or had put the cotter pin in so poorly or so undersized that it fell out when we were underway.

On my brother’s advice, we used the new, very strong, and overly long topping lift (that we had luckily insisted on installing just weeks before and had not yet shortened), as a temporary forestay. We loosened the backstay, wrestled the furler and forestay into position, and replaced the clevis pin and straightened the fork. This time I put in a cotter pin that will not come out until intended. Retightening the backstay completed the task.

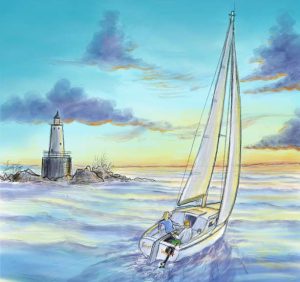

Every good sailing story deserves a good ending. The next day, we took East ‘n West downriver and ventured out past the marker buoy for the Sakonnet River entrance to Narragansett Bay, and with Newport behind us to starboard and the Sakonnet Point Lighthouse behind us to port, we declared ourselves bluewater sailors at last. Every good near-accident story also needs a good lesson, and the one that emerges from ours is the one we started with — never, ever miss checking the running rigging attachments to the chainplates after stepping the mast, and never assume someone else properly put in the cotter pins.

Every good sailing story deserves a good ending. The next day, we took East ‘n West downriver and ventured out past the marker buoy for the Sakonnet River entrance to Narragansett Bay, and with Newport behind us to starboard and the Sakonnet Point Lighthouse behind us to port, we declared ourselves bluewater sailors at last. Every good near-accident story also needs a good lesson, and the one that emerges from ours is the one we started with — never, ever miss checking the running rigging attachments to the chainplates after stepping the mast, and never assume someone else properly put in the cotter pins.

Bob and Sue Thibault call Santa Fe, New Mexico, home while splitting time in Little Compton, Rhode Island, and with their grandson in Rockville, Maryland, so East ‘n West it had to be for their Catalina 25. Bob has practiced international and U.S. energy law for many years in Denver, and Sue is a retired assistant county attorney for child protective services. Aside from very occasional boat time over the years and Bob’s long-ago sailing certification, East ‘n West is their entry into this new sailing adventure.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com