Bringing an old boat back to life provides relief in trying times.

Issue 155: March/April 2024

My husband lifted the shabby dinghy off the bed of the truck, slid the decrepit 8-foot hull onto a rolling cradle, and parked it in the driveway.

Years earlier, we had trailered our first sailboat, a 19-foot Com-Pac, into west Florida waters. Later, we owned a Nonsuch 30. But having sold that prized vessel, we were now boatless. Kirk, known to our sailing community as Captain, always maintained that part of the fun of having a boat was working on it.

“Better than mowing the grass,” he said, while wheeling the boat over to the left bay of our garage.

I recognized a restoration project when I saw it. “Where’d this come from?” I asked. “You buy it?”

“No.”

The facts came out, but not right away. I learned that a buddy at the marina needed to get rid of his stuff. The dinghy took up space in his shed — “for years,” my husband emphasized. He added, “It’s a sturdy, classic boat. Beautiful lines.”

He lightly smacked the dinghy’s port side and grinned. Was I going to support the project?

The dinghy had shown up midway through the isolation of the Covid-19 pandemic, when closed venues and masking had us spending more time at home. Our house stood at the edge of a public park. Once Kirk raised the garage door and set his machines buzzing, neighbors walking their dogs stood the required 6 feet away and curiously watched him work, shouting out questions. We learned our neighbors’ names and their dogs’ names. Sailing friends who used to meet weekly for chicken wings at a sports bar phoned for updates. It was clear that the restoration was going to bring temporary relief for everyone’s new solitary lifestyle.

The first step of the project took us to the computer for information. The dinghy was from Salty Boats of Maine, a company known for its small vessels of laminated fiberglass and choice woodworking. We talked with the company’s owners, Bruce and Cabot Trott, and from their website learned about the Salty 8’s original materials. It featured oak gunnels, knees, and breast hook, with fiberglass bow and stern seating and a midship seat of solid mahogany. A fully functioning Salty can carry a maximum load of 400 pounds, we learned.

Kirk inventoried his supplies stored above the rafters of the garage and on shelves surrounding his lathe, drill press, Shopsmith, and other machinery. It was late autumn, cool enough in Florida to work outside. He assembled his tools and materials and put in a call to the Salty factory for the knees and breast hook, components that needed to be replaced. The factory advised Kirk to build his own gunnels, since shipping the long arcs would be expensive and impractical.

The next step was assessing the condition of the hull. Kirk set the vessel upside down on the cradle. With fiberglass, he repaired the hole in the skeg and patched the cracks and blisters, then sanded the hull. After cleaning the hull, he primed it with a spray gun, sanded it further, and painted it white.

A day later, he positioned an old door on two sawhorses to make a template for fabricating the gunnels. The wood strips needed to be laminated. Kirk sketched a template and screwed the wood blocks into position about 6 to 8 inches apart. One at a time, he glued and clamped four ¼-inch strips of white oak into place. After sanding the finished assembly, he fit the gunnel strips to the dinghy’s knees at the stern and the breast hook at the bow. This step of the process took a few hours a day for about two weeks.

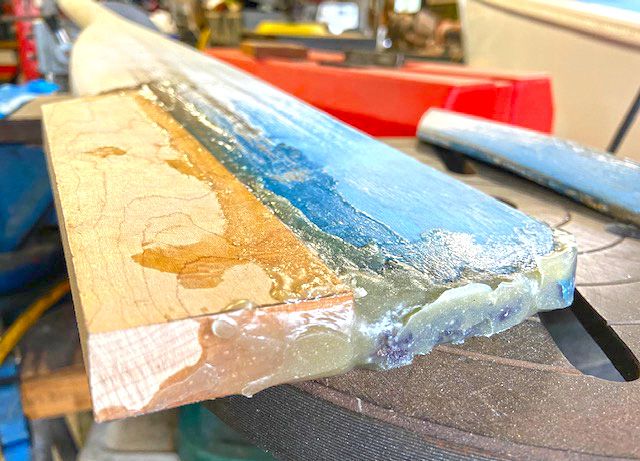

Then Kirk revamped the seats with cosmetic trim. He left the original mahogany rowing seat in place. For the stern and bow, he used bird’s eye maple and cut it to fit the molded fiberglass. He laid the wood on top of the fiberglass, adding spacers of scrap wood to achieve a perfect fit. To match the gunnels, he stained the slats in mahogany on both sides. After they were dry, he glued the slats to the seats with GE silicone caulking. The result proved visually dramatic.

“Ready for sea trials?” I asked.

“Not yet,” Kirk said. “See those oar locks? The dinghy needs oars.”

On an afternoon sortie to a marine salvage yard, we found and bought two damaged oars. Once home, I held the ladder in place as Kirk searched the rafters of our garage for pieces of white oak stored there.

“Now I know why you save everything,” I said.

Kirk fused the oak to the broken blades with epoxy resin and let the oars harden. Over the next couple of days, he shaped the new oar blades using a right-angle grinder and 36-grit sanding pad, and left them to cure. Later, he sanded the oars smooth. As a final step, to keep the oars from slipping out of the locks, he purchased an oar leather kit from West Marine. He installed the leathers on the oars, hammering them in with small brass pins. With the oars at a jaunty angle, the finished dinghy looked bright and fresh, ready for the water.

On a sunny day, we called a few friends to assist with the launch and sea trial. It was a perfect morning, with light wind and calm water. After slipping the Salty onto the bed of our sturdy Ford truck, we headed toward the local causeway. Arriving, we heard seabirds circling above the narrow beach that provided access to the Intracoastal Waterway. Our friends Ralph and Lenka unloaded the dinghy and pushed it forward, steadying it in knee-deep water. Ralph climbed in and Captain Kirk pushed him off. The Salty floated easily, even before Ralph reached for the oars. Pumping out to deeper water, he yelled back to us at the shore,

“Good balance. I’m going to head over to those sailboats at anchor.”

From our spot, we saw a captain holding a coffee cup wave from the deck of his Pearson 26 Weekender. Another sailor pulling up his anchor shot Ralph a thumbs-up. After a few minutes, Lenka’s daughter, Minnie, waded into the shallow water and jumped into the dinghy. Ralph rowed farther east and nodded back to us. Minnie called and waved. Finally, they headed in and we guided the dinghy back to shore. We agreed that the Salty proved itself a reliable and elegant vessel on the water.

Yet a final question remains. What will be next for the dinghy and for its craftsman? We realize that once a project’s done, there’s emotional loss. At the same time, the dinghy reminds us of a job well done, a vision met, and a contribution to recycling and reusing, rather than opting for the city dump.

In the garage, the boat still attracts attention from neighbors. People like learning about its history. In the near future, we will likely sell the boat or give it to a grandson for his fishing expeditions. In the meantime, there’s little chance that Captain Kirk will get bored. Recently, we drove to a friend’s backyard to check out a dilapidated 16-foot sailboat on a trailer. It came home with us and now sits on the side of the house under a tarp. There’s no hurry.

More recently, Kirk built a model sailboat from wood scraps that’s destined for Minnie’s 5-year-old brother. As always, working on a boat is better than mowing the grass.

Antonia Lewandowski, a native of New York City, moved to Florida about 30 years ago and learned to sail. She is a poet and writer, author of Tangled, a poetry collection, and Out of the Woods, a chapbook. Antonia is a 2024 recipient of the arts agency Creative Pinellas’ Emerging Artist Grant. Her poetry has been twice nominated for a Pushcart Prize.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com