Writing a cruising guide provides a new perspective on home waters.

“Just turn right at the lights,” an experienced cruising sailor told me when I first arrived in Santa Barbara a half-century ago. I was horrified how casual he was, having learned navigation in the English Channel with its fast-running tides and turbulent weather. There, one found one’s way around with Adlard Coles’ definitive cruising guides firmly in hand. They took sailors up French estuaries literally yard-by-yard and buoy-to-buoy. Their successors still do.

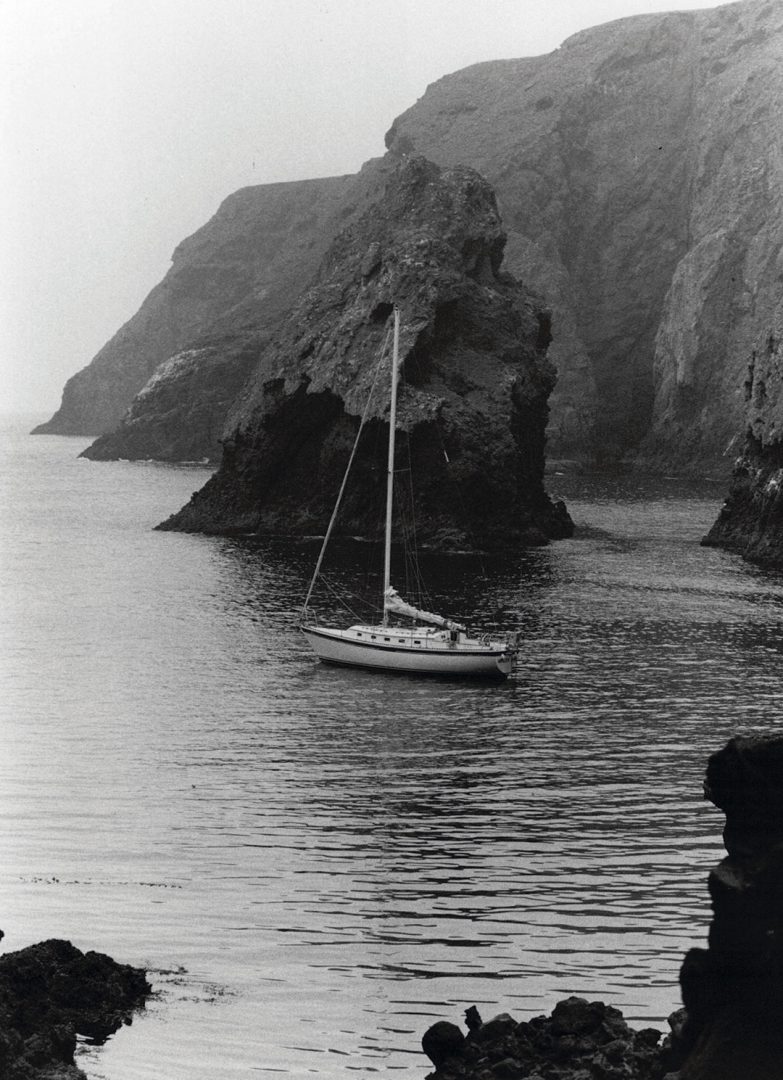

Of course, the Santa Barbara Channel is a relatively benign cruising ground with usually predictable winds and no tidal races to contend with. And yet, I’ve nearly lost my boat twice in these waters. There was a sea guide to the Channel Islands, lavishly illustrated with fine aerial photographs, but finding one’s way around the unmarked and unlit coves of Santa Cruz Island and further afield required both caution and an intimate knowledge of inconspicuous landmarks. Think the grey soil of ancient Native American middens and distinctive mainland canyons glimpsed at a distance on a foggy day, and you get the picture. At sea level with a 20-knot westerly and a reef in the main, I soon realized that a more nuanced cruising guide was an essential companion for sailing adventures here. So, I decided to write one.

It turns out that my professional experience studying stratified archaeological sites, coupled with all those years of sailing with Coles’ guides at my side, produced a highly effective mindset for compiling useful sailing directions. And, much of my longer-distance cruising off European and Mediterranean coasts had also introduced me to 19th-century Admiralty Pilots, which were still in print. Compiled in the Age of Sail by young naval officers in small sailing boats who spent months exploring anchorages, headlands, and landmarks, these joined geographer George Davidson’s 1858 classic Directory for the Pacific Coast of the United States as my models. Davidson and his surveyors traveled more than 50,000 miles in small boats, lead and line in hand. They compiled superb drawings of anchorages and coastlines that are still usable today, and gave me an excellent blueprint for starting work.

Researching and writing the guide to the Santa Barbara Channel took over 10 years and many miles of sailing. I visited every anchorage and port between 10 and 17 times in different weather conditions before finalizing the sailing directions. This was apart from writing the background essays on weather, history, and so on, which I find to be an essential part of a book like this.

Writing a cruising guide changed my perceptions not only of navigational challenges but of local geography, of the very subtle weather patterns that change with the seasons, of spectacular spring flowers on normally semiarid islands, of the places where kelp beds flourish, and of the vagaries of winter winds off Point Conception, often called the “Cape Horn of the Pacific”—and with good reason. I developed a profound admiration for ancient Native American Chumash skippers, who paddled their unique planked canoes as far west as San Miguel Island, where shrieking summer winds can beset you at anchor in Cuyler Harbor in the small hours. Reading anthropological accounts of the canoe navigators, who caught swordfish in deep water and often lost entire canoes in the windy lanes off Santa Cruz Island, one is lost in admiration at their stoic seamanship. I also developed a profound respect for my more recent forebears, not least for Richard Henry Dana and the 19th-century sailors who traveled these waters without diesel engines in weather conditions significantly windier and cooler than today.

As I developed my own local knowledge—and yes, local knowledge is a very special, hard-won expertise—I realized that a deepened understanding of my home waters added immeasurably to my pilotage skills and to my enjoyment of local passagemaking. I set out originally to write sailing directions. In the end, I wrote something much more interesting.

I also came to understand that a sober, observational mindset is the essence of a good set of sailing directions. They should be far more than merely arid descriptions of landmarks and courses to steer, or GPS coordinates. I found myself looking at the coastlines as larger tapestries. Years ago, approaching Santa Cruz Island from 10 miles offshore on a day with mediocre visibility, I gazed at the mountain peaks high up ahead. As we enjoyed a fine breeze that carried us inshore, I realized that the highest peak on the island lay directly above Fry’s Harbor, one of the finest anchorages on the island. This landmark works like a charm, as does a low point that lies behind Prisoners Harbor, the major landing place slightly to the east.

Call this local knowledge if you like, but I learned my coastal navigation and Santa Barbara Channel waters long before the days of GPS and chart plotters and am glad I did. I remember once sailing out to Santa Cruz with a friend with a newfangled GPS years ago.

“How far off West Point are we?” he asked.

“Seven miles,” I replied.

The machine proclaimed it was 7.1 miles ahead. My friend was suitably impressed, but I had years of looking for local landmarks informing my navigational understanding.

These days, some might ask, why not just rely on GPS? I would argue that apart from the hoary old caution of unreliable electronics, you may know where you are within a few feet, but you still need conspicuous and inconspicuous landmarks visible at a distance or close to shore. You can probably rely on just GPS or a chart plotter when approaching places like Catalina Island, but there are other waters where paper and electronics go best hand-in-hand. Try navigating in shallow waters through the Bahamas or making your way through Baltic archipelagos where every island looks the same. The Swedish government charts come in flip format, each sheet covering a few miles. You must always know where you are visually within a half mile or less, GPS or not, or you’ll be helplessly lost.

Visual cues are still a necessary element of navigating. A good case in point is the low-lying shoreline of Channel Islands Harbor and Port Hueneme as seen when approaching from the sea. A conspicuous power plant with a single stack lies north of the harbor. Don’t confuse it with another power plant with two stacks to the south. I found this out on a day when a strong post-frontal westerly was propelling us toward what was a then-to-me-unknown lee shore at dusk. Or, if you want to explore Lady’s Harbor on the north coast of Santa Cruz, you need to look for a patch of gray soil—seabird droppings—on the east side of the narrow entrance. Call me old-fashioned, but even in relatively straightforward waters like Southern California’s, I always ship out with a chart.

The joy of cruising my home waters lies not only in passagemaking, but also in the art of anchoring. And I use the term art on purpose, an art learned by hard-won experience lying in confined spaces and crowded bays, by dragging in the middle of the night, and by setting anchors bow and stern, essential in many Channel Islands anchorages. All the author of a guide can do is make suggestions. British Admiralty Pilots use wonderfully precise expressions. My favorite of their dictums is “anchorage may be obtained.” How true! You obtain an anchorage by careful judgment of local conditions when you arrive, nothing less. No author can do this for you.

Which brings up the final point. Cruising guides are, in essence, sailing directions, which are based on the assumption that the reader will make seamanlike judgments on the spot. I was criticized for being “too severe” in the first edition of my book, but I’m unrepentant, despite softening the language in the next iterations. There are anchorages in our waters that are literally suicidal in strong westerlies or northeasterly Santa Ana wind conditions. All I can do as an author is remark that such-and-such anchorage is “dangerous” in southeasterly gales. It’s up to the sailor whether to take my observation at face value. Seamanship is all about judgment. So are cruising guides as basically simple as mine or as elaborate as Adlard Coles’.

My guide has been in print in various editions since 1979 and is still widely used. It has been immeasurably improved by comments from users, who take the trouble to make constructive suggestions or to correct the inevitable errors. You have to have a thick skin, for there are readers who get pleasure from abuse and being rude, some of them, alas, sailors. Such critics forget that these are not books one writes for money. You write them as a service to others having earned your experience the hard way.

Directions for Sailing Directions – BF

Writing a cruising guide is not as easy as it seems, even with thousands of miles under your keel. Following are some hints on writing actual sailing directions, not background chapters, that I learned the hard way.

Cultivate an enduring curiosity and a mindset that depends on precise observation. Anyone can look up a position or a course these days, but what makes the real difference are your observations from sea level, made when you are sailing.

Select landmarks that are visible at a distance or when close inshore. Many will be unchanging features like mountain peaks or prominent headlands. Others will be humanly constructed, such as a hotel building, a conspicuous feature like a freeway trestle, a lighthouse, or a factory building. Think colors. They can stand out more than the building itself. Small wonder that Admiralty Pilots refer frequently to conspicuous structures, shown on large-scale charts as “Conspic. White Ho.” But wouldn’t you know it, someone will invariably paint a prominent structure once we’ve all gotten use to navigating based on its color!

Adapt a relatively standardized format, which starts with general remarks, then describes the approach from different directions, followed by the entrance to the port or anchorage, then anchoring or berthing information. This makes the book much easier to use.

Keep your style brief, economical, and logical. Remember that a skipper will often consult these directions in less than ideal weather.

Be precise. It’s no use saying, “Anchor close to the beach.” Instead, try this: “Anchorage may be obtained in 25 to 30 feet with the yellow cliff on the east side of the anchorage about 150 yards ahead. Beware of seagrass on the sandy bottom.” All the information the visitor needs is there.

Provide clear drawings and photographs, the latter taken from your deck. These are literally worth a thousand words and, if well-chosen, will save a thousand words. You’re best off if you take the pictures on a calm, clear day. If you get several days of ideal photographic conditions, rent a motorboat and try and shoot as many anchorages as possible over a sequence of calm days.

Don’t spend too much effort on detailing modern facilities ashore—they change all the time. Ask a local for the latest! But modern navigational aids like light buoys and lighthouses are another matter; emerging from a thick fog as evening gloom deepens and seeing a flashing light where it should be always fills me with a profound and inexpressible relief.

Above all, be accurate, as entertaining as possible, and listen to other sailors and critics. They often (but not always) know more than you do.