A winged visitor catches a ride on a glorious late summer sail

Issue 152: Sept/Oct 2023

Early on a brisk September morning, as we motored out past the Absecon Inlet jetties on our way offshore and left Atlantic City, New Jersey, behind, the sky held my attention. It was a riveting crystalline blue, almost electric. The dry air that comes with northern fronts seems to produce this amazing atmospheric clarity. Where we live, near Houston, Texas, and the Gulf Coast, there’s typically enough humidity that the sky is muted in comparison.

Our timing was especially good, as the remnants of the front gave us winds out of the northwest at a steady 15 to 18 knots. We motored well clear of the jetties and the coastline and rounded up into the wind to hoist the mainsail. After turning southward, we unfurled the jib and off we went. We were beam reaching in 3- to 5-foot seas, consistently making more than 7 knots and occasionally touching 9, with both the seas and current in our favor. Our course to Cape May was roughly due south and about 40 miles, jetty to jetty.

With only the Atlantic Ocean between us and the two inlets, it promised to be a glorious day. As a bonus, the surrounding ocean was a deep, inky blue, more steeped in color than the blue sky above. Also aboard our 1987 Sabre 38 MKI, Orion, was my wife, Kris, and a good sailor and friend, Nick Stepp, from Houston. Nick and his wife, Laura, co-own with another couple a Nonsuch 30 that they keep on Clear Lake, south of Houston. While Kris and I are comfortable sailing doublehanded, we were grateful for Nick’s presence, as another person onboard can be positive in so many ways.

Just before noon, a winged visitor showed up unannounced. It is not uncommon for birds, usually small birds such as swallows or wrens, to land on offshore boats for a brief rest. Amazingly, these birds are typically so unafraid of the boat that they will land on the people who are sailing it. You can often get very close to them without any reaction from the birds, and on occasion, they will perch on a knee or a shoulder. This has happened to me several times on sailboats, and I can only imagine the need for rest overcomes their well-founded fear of humans.

This bird appeared to be a juvenile kestrel, also known as a sparrow hawk. It is the smallest and most common falcon in North America — not something you see every day offshore. It was obviously very tired and must have been inadvertently blown offshore by the front. The wayward kestrel landed near the stern and was struggling to stay attached to the boat, as the fiberglass was much slicker than any tree branch. The wind was gusting and ruffling the bird’s feathers.

Suddenly, it flew back into the air and turned toward shore, but soon faltered and dipped low to the water, then wheeled around and attempted to fly back to Orion. Alternating between flapping its wings and coasting with the wind to save energy, it seemed to want to come back to the boat, but the distance was not closing. It looked as if the effort to regain contact was going to be too much. We were all riveted on the scene and rooting for the bird to make a successful return.

At last, the kestrel landed again on a spot near the stern. Everyone, including the bird, breathed a sigh of relief. Then, as if realizing its position was tenuous and it needed to find something less slippery to hang onto, it flew up under the dodger and settled onto a coil of line. It stayed there for the better part of an hour, keeping a careful watch on the three of us in the cockpit. We were thrilled that it was momentarily safe, and wanted to do all that we could to help this young bird survive. We kept our movements to a minimum and did not even venture belowdecks, since the companionway hatch was so close to the bird’s perch.

Suddenly, the kestrel took flight again, heading on a diagonal course toward land. As it did before, whether by design or just due to sheer exhaustion, it flew very close to the tops of the waves. We tracked its progress until the waves finally blocked it from our view. It was a bittersweet moment, knowing we probably helped save its life once, but also fearing the worst.

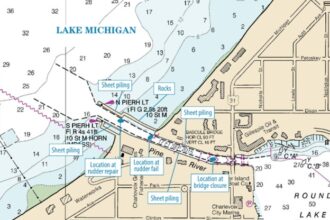

Our glorious day of sailing continued until it was time to jibe toward the Cape May jetties. Once inside, we furled the sails and motored west a mile or so to a popular anchorage in Cape May Harbor adjacent to the Coast Guard station. There were already a dozen or more boats in the anchorage, and we found a spot near the back of the fleet to drop the hook.

As the day neared its end, the sun was a brilliant orangehued ball hanging near the horizon. A band of low clouds stretched across the sky and picked up the colors from the setting sun. A gentle breeze rippled the darkened water. There were sundowners and dinner to look forward to, along with the warm feelings that come from an exhilarating day on big water. We would most certainly talk about that beautiful kestrel who shared a part of our wonderful day and fervently hope that it was safely back on land.

David Popken and his wife, Kris, have owned two good old boats since purchasing a 1978 Hunter 30 in 2002. They bought their Sabre 38MKI in 2012 and have cruised the Gulf of Mexico and Eastern Seaboard extensively, with side trips to the Bahamas. Their home port is Seabrook, Texas, but Orion is a wanderer and is currently berthed on the Back River in Hampton, Virginia.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com