Why taking care of things big and small on your boat makes a difference

Issue 152 Sept/Oct 2023

Perusing a Craigslist ad for a 40-year-old, 40-foot sailboat, I laughed out loud when I read, “Everything works!” I said to myself, “I want that boat!”

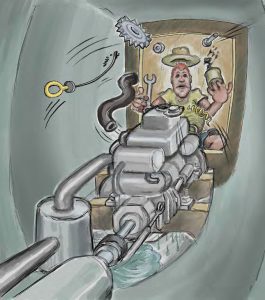

Being the owner of a 50-year-old sailboat, I know how rare and wonderful it can be to have everything work. Currently I have a leak in my fuel line, one LED light doesn’t work even though the ones before and after it in the electrical daisy chain light up just fine, a dimmer switch has packed it in, and there’s a leak around the mast collar and another small one in a deadlight. And that’s just the stuff down below that’s on my list. On deck there is even more to attend to. My wife has a list of her own.

Five years ago, almost everything on our 1971 Columbia 43, Oceanus, was brand new. A previous owner gutted the old girl and started an ambitious rebuild and refit that he pursued for three years before a bout with cancer caused him to sell the boat. After we bought it, I thought it would take another 18 months to get her ready to cruise. It took twice that.

Five years ago, almost everything on our 1971 Columbia 43, Oceanus, was brand new. A previous owner gutted the old girl and started an ambitious rebuild and refit that he pursued for three years before a bout with cancer caused him to sell the boat. After we bought it, I thought it would take another 18 months to get her ready to cruise. It took twice that.

When we bought any piece of gear, it was the best we could find and usually brand new. Even then, a shocking percentage of the gear didn’t work right out of the box. But finally, we declared Oceanus finished, which was more a decision than an actual state of being. The truth is, a cruising sailboat with all of her complicated systems — propulsion, steering, sailing, electrical generation and storage, electronics, navigation, plumbing, waste management, the list goes on — is never really finished.

Then comes the real mother: Mother Nature. And entropy — or what scientists call “The Red Queen Problem.” The name comes from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, when the Queen of Hearts says to Alice, “… we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that.”

A more sinister and humorous take is resistentialism, a theory positing that inanimate objects exhibit hostile behavior toward humans. Coined by British humorist Paul Jennings, the term blends the Latin res (thing) and French résister, (to resist) with existentialism. The slogan of resistentialism is “Les choses sont contre nous” or “Things are against us.” While it often seems that way to me, especially with electrical and plumbing issues, there’s nothing to do but surrender and fix the darn problems when things break, leak, or simply don’t work. A better approach, however, is one I learned from my grandfather.

My grandfather kept a small herd of cattle, rising every day before dawn to feed them. He counted the cows as they gathered around the bales of hay. With a practiced eye, he would check each cow and calf. Then he would feed the bull and the steers, watching as they walked and ate. If he saw a problem, he attended to it as soon as he could. After feeding the herd, he did something to improve his pastureland, fence line, or stackyard, or attended to the hundred other things that needed doing on his land.

At the only cafe in the town where my grandfather lived, one old boy told me he wished he could get as much done in a day as my grandpa. Yet grandpa always had time to have coffee with the boys or take us kids out to the flat to see the cattle.

My grandpa was a good husbandman to his cattle. He did something every day so things didn’t get out of hand. If I am to have any hope of getting ahead of the Red Queen Problem, or at least keeping up, I need to follow his example and do something daily to improve the boat — not just to repair it, but also to prevent problems. I tried to do that during our two-year voyage from Oregon to Southern California, Mexico, and Hawaii. We were pretty successful at it. Oceanus looked good and most things worked most of the time.

My grandpa was a good husbandman to his cattle. He did something every day so things didn’t get out of hand. If I am to have any hope of getting ahead of the Red Queen Problem, or at least keeping up, I need to follow his example and do something daily to improve the boat — not just to repair it, but also to prevent problems. I tried to do that during our two-year voyage from Oregon to Southern California, Mexico, and Hawaii. We were pretty successful at it. Oceanus looked good and most things worked most of the time.

It was fun, too. About once a week, my wife and I would grab a rag and a blue scrubby (Pro tip: the blue ones don’t leave scratches like the green ones). We would jump into the warm, clear water of the Pacific and give the old girl a scrub. We called it our yard work. It kept our boot stripe from looking scummy and prevented grass and other growth from fouling her bottom. Looking down, we watched spotted eagle rays and schools of jacks swimming by, or goatfish and puffers nibbling at tasty crustaceans uncovered by our anchor chain.

Sunny mornings were best for getting something done on deck or working on the rig. Even crawling into the engine room wasn’t so bad before the day got too hot. Following up with a soak and a snorkel mitigated even a dirty, nasty job.

Keeping the Red Queen at bay is more challenging now that we are living the easy life as liveaboards in a nice marina in Washington state. We don’t take the boat out as much and we don’t have to be constantly on guard, ready to move anchorages if a Kona wind blows up. I confess, I’ve let things slip.

To make matters worse, my wife and I recently finished building a small apartment above my son’s garage. It’s a refuge for us during the worst of the dark, cold, “North-wet” winters. It’s only about an hour away from the boat, but the distance does limit our boat work during the winter. We visit Oceanus at least once a week and work on our list. Still, not living aboard full time does make it easy to let the Red Queen have her way.

A few years back, a Jeanneau 42 moored a few slips down from us in an Oregon marina had seagulls nesting on its radar arch. You would need a snow shovel to clean out the guano, feathers, and shells in the cockpit. The seagull couple raised three chicks on the boat one summer, and the Portland attorney who owned the boat — and whom we never saw — was none the wiser.

I joked with my wife that I should mock up some U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stationery and notify the owner that his boat had been declared a seagull sanctuary and he was not allowed aboard until the chicks fledged. That would get him down to his neglected boat, I thought.

I joked with my wife that I should mock up some U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stationery and notify the owner that his boat had been declared a seagull sanctuary and he was not allowed aboard until the chicks fledged. That would get him down to his neglected boat, I thought.

As much as we joked about it, my heart hurt for the Jeanneau. Under all that guano was a beautiful boat that someone, at one time, loved. Boats are about as close to a living thing as any inanimate object can get. They move, groan, are temperamental at times, and have unique personalities. They also need to be cared for.

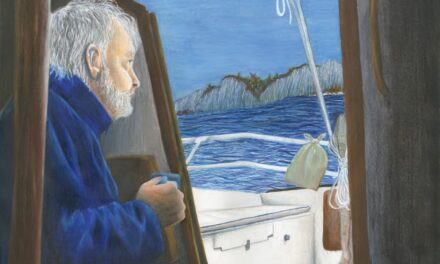

It’s easy for me to believe that boats have a soul or spirit. Even when singlehanding, I never feel alone. I hear the boat conversing with me. I hear or feel what she needs through the nudge of the tiller or the rustle of a sail. Boats, more than almost anything else made by man, are infused with, as D.H. Lawrence wrote, “Soft life … (and) are awake through years with transferred touch, and go on glowing … with the life of forgotten men who made them.”

I often think about those men who built my boat half a century ago. I would like them to see it now — still sailing, still a comfortable home, well loved, and ready for another 50 years, despite the Red Queen.

Brandon Ford, a former reporter, editor, and public information officer, and his wife, Virginia, a registered nurse, sailed from Newport, Oregon, to California and Mexico, and then spent 13 months cruising seven of the eight main Hawaiian Islands during 2016 and 2017. Before their cruise they spent three years refitting their 1971 Columbia 43, Oceanus. Lifelong sailors, they continue to live aboard Oceanus part time and cruise the Salish Sea from their moorage in Olympia, Washington.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com