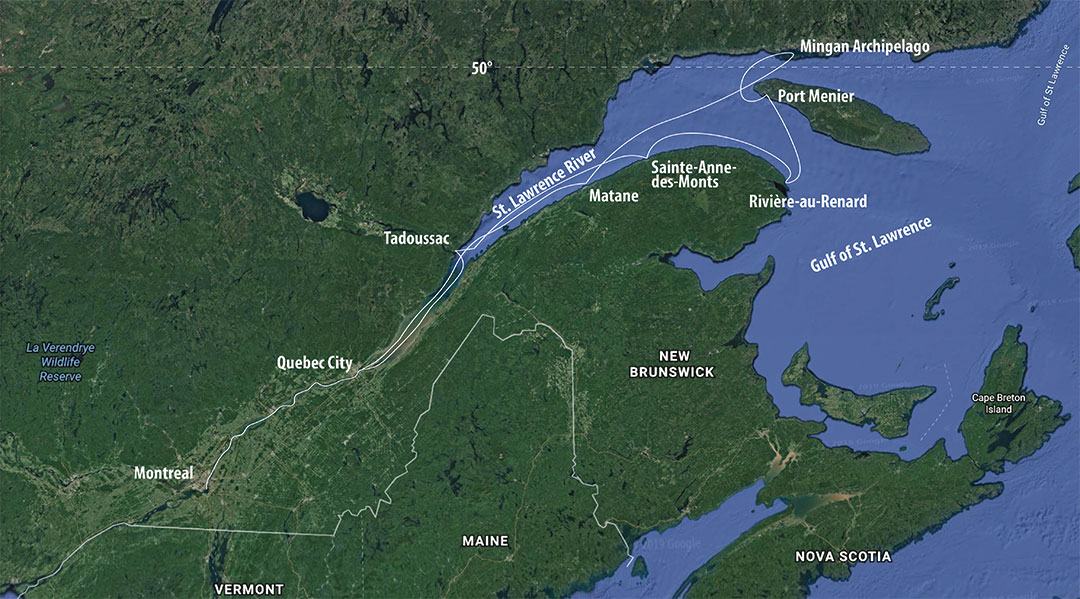

A singular voyage leads to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence’s stunning Mingan Archipelago

It was on the way back from a trip to Tadoussac—a fun adventure from Montreal on Exilés, my Southern Cross 28—when my friend and crewmate, Robert, casually tossed me a brochure and said, “Here. Dream a little.” The brochure was about Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve, a group of spectacular, otherworldly islands in the eastern area of Quebec, Canada, on the north shore of Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

It’s a good 600 miles from my home port near Montreal, through challenging, chilly waters and across the 50th parallel, a not insignificant, time-consuming bit of sailing. I thought at the time that this was far-fetched and unrealistic, but somehow all the pieces fell into place a year later, and this 1,200-mile, two-month odyssey confirmed for me that little Exilés is suited to take me and my crew anywhere safely and comfortably. It was a voyage marked by breakdowns, record heat, numbing cold, thick fog, overnight passages, strong winds, tidal currents, and busy shipping lanes. From it all, we have great memories and stories to tell, and plans for the next great adventure are already brewing.

It began inauspiciously. With my wife, Liuyuan, and our talkative African Grey parrot, Smokie, we’d barely gotten a few miles beneath our keel before I was below, contorted around the engine. As we’d approached the Côte Sainte-Catherine lock (just across the Saint Lawrence River from Montreal), our engine’s exhaust manifold pipe sheared off. Not only did this happen on a Sunday, but it was July 1, Canada Day, a national holiday. Nothing would be open. I think it was here that Smokie added a few more words to her vocabulary.

I made one call to my heroic brother, Christian, and he had a roll of high-temperature-resistance duct tape to the boat before we reached the next lock. This temporary repair got us through the next few days, during which favorable currents and winds carried us straight on to Quebec City, where I had the exhaust manifold replaced. The mechanic told me that after we put several more hours on the engine, I should check the two bolts securing the manifold to the engine.

Quebec City was the end of the first leg, and all that Liuyuan (and Smokie) could commit to before returning home. Christian joined me for the next leg, defined by the two weeks he could spend aboard.

Soon after leaving Quebec, we stopped at Marina Saint-Laurent on l’Île D’Orléans (now referred to as Club Nautique de l’Île Bacchus) to wait for the tide to reverse so we could keep riding the strong ebb and not fight the flow. Despite the dropping temperatures of the water and the air, Christian and I braved a quick swim before bed. To catch the ebb, we’d need to get back underway at 0300. Unfortunately, during the night, the winds howled and the boat was uncomfortably rocky; neither of us slept well. And at 0230, we were on deck in hats and gloves, two guys in their 50s retrieving a 35-pound CQR in total darkness and choppy water.

One hundred miles east we stopped at Tadoussac, a village at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence River and the Saguenay Fjord. Founded at the start of the 17th century, it served as the center of fur trade between the French and First Nations peoples. In the 19th century, tourism became the primary draw and remains so today, particularly whale watching. The settlement is very small, the area rugged and rural.

We’d found getting across the river to Tadoussac with the right timing a tad tricky, with particularly strong ebb cross-currents from both the Saint Lawrence and Saguenay. We were moving backwards at one point. It all worked out in the end, and we rewarded ourselves with a fish-and-chip lunch at the marina’s restaurant upon arrival.

East of Tadoussac things grew increasingly wild and undeveloped. We’d radio the coast guard each morning with our planned route. When we arrived someplace for the day, we’d call and close our plan (and when we’d forget, they’d promptly call us)—a great service! In this part of the river, we saw lots of whales and seals but also in some cases a great number of fast-going sightseeing boats, which tainted the experience.

In Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, I put a wrench to the two bolts that attached the new exhaust manifold to the engine. One tightened a bit, the other just spun! The stud was stripped, and I didn’t have a spare or the tools to make one. But this misfortune served as a reminder that on adventures it’s the people you meet who stick with you, long after the memories of place recede.

Sylvain, the marina’s attendant who looked as if he descended from a long line of tough-as-nails seamen, turned out to be the friendliest and most resourceful guy we met. He connected us in no time to Yvan Pelletier, an 81-year-old mechanic who removed our stripped stud from the engine on very short notice one evening, brought it to his pristine shop overlooking the Saint Lawrence, and meticulously machined a new stud for Exilés’ manifold. We were back in business.

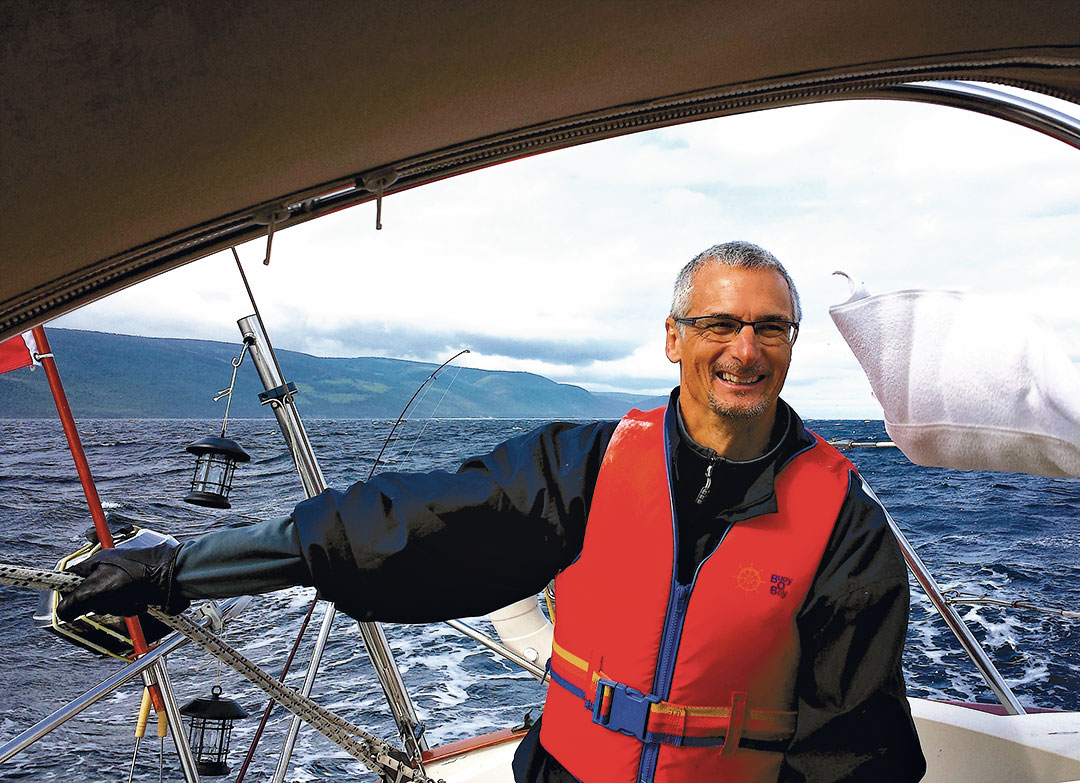

The next day, the tempo increased. Leaving Saine-Anne-des-Monts, the Saint Lawrence River opens wide to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. As we prepared for a sail along the northern side of the Gaspé Peninsula, the Canadian Coast Guard issued a small craft warning with 20- to 25-knot westerly winds and 6-foot seas. For us, this meant an exhilarating sail between Sainte-Anne-des-Monts and Grande Vallée. Exilés was in her element. Despite being knocked around a little and tackling some carefully controlled jibes, we had a blast. After dropping the hook in Grande Vallée, we sat and relaxed for hours, watching the northern gannets (fous de bassans) dive for fish; what a show!

From here we could have turned north and headed directly for the Mingan Archipelago, but Christian had to catch a bus home. So, we set our Cape Horn self-steering system and continued east, following the coastline along the top of the peninsula, and headed for Cape Gaspé. It was a real treat for the two of us to sit comfortably on the foredeck while Exilés steered herself.

When we finally arrived at Club Nautique Forillon at Rivière-au-Renard, we found a colorful and busy fishing port that included a small marina. Mary-May has looked after the marina since setting it up 27 years ago and still welcomes all visitors as though they are family. Here, Christian boarded a bus for a 15-hour ride home, and the next morning, my friend (and crew for the next four weeks) Robert arrived on the same bus.

Robert and I left Rivière-au-Renard and headed due north for 50 nautical miles across the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to reach Port Menier, on Anticosti Island. This was my first experience far enough offshore to not see land for several hours. I loved it—until the porpoises left and dense fog arrived. At one point we couldn’t see beyond 50 feet or so. We didn’t have radar, and I was busy on the VHF ensuring our position was known to ship traffic in the area.

Anticosti Island is one of Canada’s largest, ranking 20th in size, and, with over 400 shipwrecks along its shores, it is often referred to as the cemetery of the Saint Lawrence. Only a few hundred people reside on the island, along with over 100,000 deer and a healthy population of mosquitoes. French chocolate maker Henri Menier bought Anticosti Island in 1895 for use as a game reserve, as well as for logging and cannery operations. Port Menier was the center of these operations and is today the hub of Anticosti life. Menier was a notable sailor who crossed the Atlantic numerous times to visit his island, on which he kept a 30-room, Scandinavian-style mansion.

Robert and I were so taken by the charm and people of Port Menier that we spent an extra day there, walking about, chatting, and learning more about this place’s history. But the Mingan Archipelago was the ultimate destination for this adventure, and we were only one more Gulf crossing away.

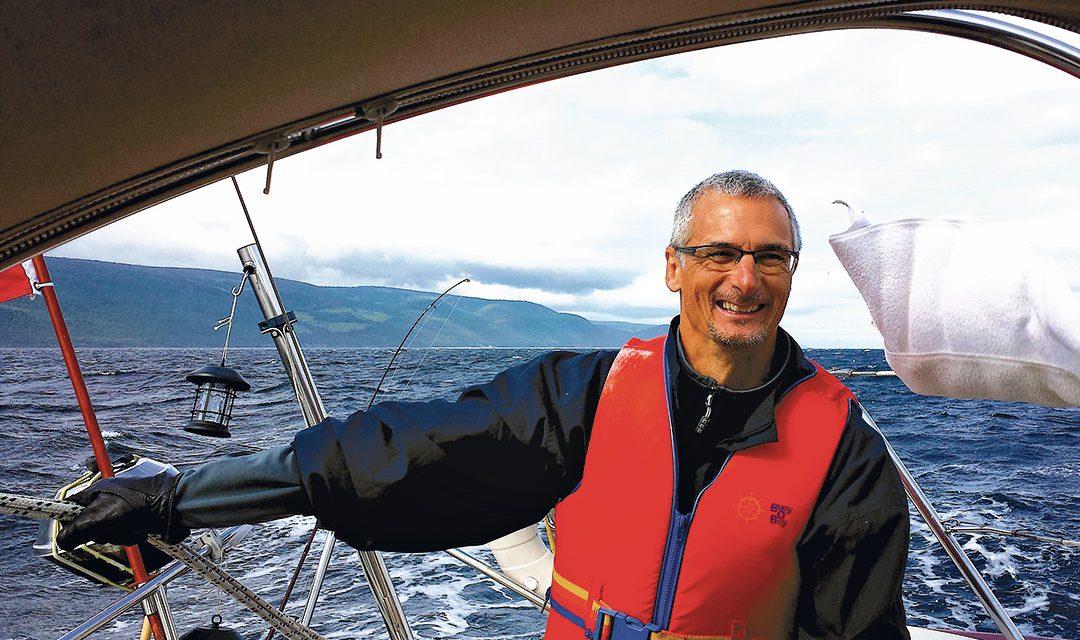

From Port Menier we rounded the western tip of Anticosti Island before turning north, across the 50th parallel, to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence’s north coast, where the cold Labrador Current runs. It started as a rocky sail with a strong breeze and lively chop, and I didn’t have much of an appetite for our breakfast-on-the-go. I’m normally a fast eater, and Robert chuckled at how slowly I chewed my eggs and bacon.

Crossing the 50th parallel, which lies between Anticosti Island and the Mingan Archipelago, was a great achievement for Robert and me. In a way it was just a “5” followed by a bunch of zeros on our chart plotter, and fog was all around us at the time, but the feeling of accomplishment was very real, and we were in a great mood.

As we approached the western-most island of the archipelago, fog shrouded the islands from view, but all around us we could hear whales surfacing and breathing. Once we dropped the hook, we opened a single-malt scotch-whisky that I had reserved for crossing the 50th and reaching the archipelago.

We spent six days in this unspoiled treasure, a place of spectacular beauty and fascinating geography and ecology. This reserve is comprised of about 40 islands featuring eroded limestone monoliths, rare plant species, fossils, and many types of seabirds. Standing next to the monoliths was humbling and decidedly more satisfying than anything I had imagined looking at the glossy brochure that Robert had tossed at me a year before.

We had the chance to explore two of the archipelago’s islands, Quarry and Niapiskau, with friendly and enthusiastic guides from Parks Canada. We spent time with the guides before and after the visits and got to appreciate their own perspective of life in this remote area. They explained how the impressive limestone monoliths were formed through erosion over thousands of years following the retreat of the last ice age. The islands’ unique microclimate has allowed a rich variety of plant life to thrive here (such as Labrador tea leaves), as well as scrawny evergreens that live to 200 years, twice the lifespan of the same trees on the mainland.

Along with the stunning natural beauty, we met wonderful people. We spent a day in Havre Saint-Pierre, a quaint Acadian town of roughly 3,500 people on the Gulf’s north shore in the heart of the archipelago. Proud and welcoming Acadians were quick to share their stories, including Monique, the marina’s attendant at Club Nautique de Havre Saint-Pierre. Membership fees at this club are a fraction of what we’re used to in and around Montreal, so it took (and still takes) some willpower not to settle in Havre Saint-Pierre!

The Acadian accent took a bit of getting used to, but I feel all the richer for it, as the Acadians’ colorful history formed an important fabric throughout many parts of North America. I’m not normally a highly social creature, but these interactions were for me far more powerful than any book, magazine, or brochure.

We felt especially privileged to be among the few sailors, even from Quebec, who come here to explore. We were a bit surprised that all the sailors we met transiting via Rivière-au-Renard were headed south rather than north to Anticosti Island and beyond to the Gulf of Saint Lawrence’s north coast. Certainly the climate there is on the cooler side, especially when 25° C (77° F) is considered to be unusually hot—leading to a lot of fog since water temperatures are barely above freezing—but to us this made it all the more appealing by way of escaping the heat and crowds of our cities in summer.

It was hard to turn for home, but a month had passed since Liuyuan and I had left Pointe-Claire. Robert and I made several small passages—one 24-hour run, which was my first overnight sail—as we made our way from the Gulf back into the Saint Lawrence River. The highlight of the voyage home was the village of Matane, where Robert and I spent three days immersing ourselves in the local charm of this historic town, a trading post from the early 1600s. We spent many hours chatting with fellow sailors from the town’s small but quaint marina.

For example, we met Pierette and Clermont aboard their impeccably home-built and superbly maintained 34-foot wooden sailboat Fleurion, which they’ve sailed for many years, including no fewer than six Atlantic crossings. It didn’t take long for us to feel at home in Matane; as in Havre Saint-Pierre a week before, it wouldn’t have been difficult to remain right there and become “Matanais.” Alas, schedules and other commitments suggested otherwise. As we left Matane on our way back toward Montreal, Clermont stood at the end of our slip waving goodbye until we were out of sight. Memories from these shores remain, subliminally but persistently tugging me to return as if this is where I belong.

Robert stayed with me for several stops more until we reached Port of Quebec Marina where he caught the bus back to Montreal after four great weeks with me aboard Exilés. On his heels, my son, Paul, joined me for the final leg home to Pointe-Claire. Though we didn’t have far to go, this would by far be the longest sailing trip Paul had been on, and I looked forward to sharing it with him. We made several stops, and then on Aug. 24, 55 days after leaving, Exilés made it through the Montreal locks and back to Pointe-Claire by supper time.

It was bittersweet. On this adventure, living aboard Exilés came to feel increasingly “right.” Though all my days aboard were different, they shared a rhythm. Life was distilled to discovering a new place, meeting new people, challenging myself on the water, taking pride in passages completed, and anticipating the next landfall. It is something I could do more of.

Fortunately, each of the four crew who joined me along the way are keen to return and repeat a similar experience—some wishing to undertake even more ambitious exploits—and we are already planning new adventures. I’m not sure if it would be more thrilling to return to this spectacular area, with so much more to explore, or to embark on a whole new voyage elsewhere in northern waters, but I’m hooked either way.